Six members of the CWW travelled to Cognac, France, from 9th-12th April, 2018, to visit Cognac producers from the designated growing areas of Charente-Maritime, Deux-Sèvres and Dordogne. As well as meeting some wonderful people, the group experienced some exceptional cultural and gastronomic experiences. A special thank you goes to our member Liz Palmer and the BNIC (Bureau National Interprofessionnel du Cognac) for organising this amazing trip. The reports were written by David Copp (UK), David Kermode (UK), Jürgen Schmücking (Austria), Charlotte H.M. van Zummeren (Netherlands), and Liz Palmer (Canada). Photography by Jürgen Schmücking.

An introduction to Cognac

Among other discoveries, Liz Palmer learns that almost all Cognac is exported, at the group’s briefing at BNIC.

On our first day, David Boileau, Ambassadeur du Cognac au BNIC, gave us a presentation which included an overview of the Cognac production process, grapes, grades, producing regions, and 2017 export and economic figures. This all took place at BNIC’s offices which was followed by a detailed tasting.

Six interesting takeaways are:

- 97.8% of Cognac produced is exported.

- 197.4 million bottles of Cognac were exported in 2017, resulting in a turnover of €3.15 billion.

- Cognac is marketed to over 156 countries;

- Cognac’s 10 main markets are: USA, China, Singapore, UK, Germany, France, Latvia, Hong Kong, Holland and South Africa.

- Cognac exports have continued to grow in 2017 (for three consecutive years).

- In terms of style, VS Cognac accounted for half of Cognac shipments, with volume growth of 8.6%.

The temperament of Cognac making: a visit to Jacques Denis

David Copp soaks up Cognac’s sleepy atmosphere and finds it’s the ideal environment for allowing the sublime spirit to mature in peace.

Cognac Jacques Denis is a small family-owned and run distillery in St. Preuil, a few miles south of Jarnac, in the heart of the Grande Champagne region, the premier growing region of Cognac.

The gently hilly countryside has few distinguishing features. In fact, its chief characteristic is an air of somnolence, encouraged by sleepy little hamlets of stone-built houses, roofed with weathered tiles, and fronted with drawn shutters. Which is very fitting indeed because fine old Cognac takes time to develop and prefers to do so in peace and quiet. Indeed, Grande Champagne eaux-de-vie, like the first growths of Bordeaux, take time to mature. It really does repay distillers and blenders for their love, care and attention, when great Cognac is given time in trusty old Limousin oak.

The assemblage is the work of a creative genius with a nose. The result is a fine spirit which sells to connoisseurs around the world for between £100 and £600 a litre. The distillers must be doing something right because the latest full-year sales statistics show that the export market for such fine Cognacs is growing.

Cognac is an extraordinary story because it starts with Ugni Blanc, one of the world’s most commonplace grape varieties, better known as the Trebbiano of Italy. However, Ugni Blanc is favoured in Cognac, because it retains its acidity longer than other white grapes and is relatively low in alcohol – factors of great importance to the distiller wanting a fresh and fruity base wine to work with.

Grande Champagne is the preferred region for grape growers wanting to make fine, elegant, well-structured, diaphanous Cognacs. The Denis family specialises in making artisanal Cognacs. They live and work at the very the heart of the most famous Cognac region and have applied their skill and artistry to turning the fruit of the ordinary Ugni Blanc grape variety into an enticing eau-de-vie, for over 150 years.

The family home is a handsome old farmhouse rather than a grand mansion. Built in local stone, it has stood the ravages of time: and looks as if it will be able to withstand further ravaging. It sets the tone of our visit. Little is left to modernity here. Rightly so because the factors that really contribute to great Cognac are terroir, temperament and time.

The soil is largely Upper Jurassic – a limestone base rock washed with sedimentation brought down from the Massif at the end of the Ice Age. Charente is squeezed in between the Atlantic and the Massif Central and the climate is mild and gently humid. By temperament, I mean the calm, the patience, the creative genius to visualise what they want to produce – truly fine eau-de-vie. Great distillers know when to separate the heads and the tails at distillation, they know which barrels to select for maturation, they know how to harmonise different distillations and how long to leave their eau-de-vie in peace and quiet in dark, humid cellars.

M. Denis prepared for us a tasting of his Grande Champagne Cognacs at 10, 20, 30 and 40 years of age. I was impressed by their lack of flamboyance. They were generous Cognacs made with heart but I found their balance, elegance, finesse and subtlety extremely appealing. The point about ageing was well made. The Tres Vielle Grande Champagne sells at around €600 a bottle.

One of the most important things I learned during our visit to Cognac was how to taste and drink Cognac properly: how to appreciate aroma without swilling the glass white wine style; how to allow the palate time to assimilate flavour; and how to savour the long and lingering aftertaste. The tasting at Cognac Jacques Denis was an inspired choice by the visit organisers and quite made my day.

The art of the blend: visiting Rémy Martin

David Kermode discovers why Rémy Martin gives creative freedom to the cellar master and that Carte Blanche tastes ‘incredible’ with the finish ‘a never-ending story of posh gingerbread men’.

Nothing happens quickly in Cognac. Sitting on the Charente river, the town is beguiling, its charms bucolic. Even the youths hanging around McDonald’s exhibit a relaxed form of feral. There’s plenty of money to be made from the superior brandy to which it gave its name, but it’s anything but a fast buck. It’s all about ageing … and patience.

It’s also about consistency, of course. Just as Champagne relies on reserve wines and master blenders to create a distinctive and luxurious house style that’s immediately recognisable, so too does Cognac. The difference is that a cellar master may never actually get to release his or her carefully crafted creation, trusting it instead to the next generation. At Rémy Martin – the third of the ‘big four’ Cognac houses, by size – that’s what’s happening now, with the release of Carte Blanche Merpins Special Edition. This is a limited release of Fine Champagne Cognac, from deep within the company’s sprawling cellars, with a minimum age of 27 years. Remarkably, what’s in the bottle is only slightly younger than the man now responsible for it: cellar master Baptiste Loiseau.

Eyebrows were raised when Loiseau took over in 2014, at the age of 33, the youngest person ever to hold such an esteemed role in the lofty world of Cognac. He was no upstart, having spent the best part of a decade under the tutelage of his predecessor, Pierrette Trichet – the first woman to be made cellar master of a major house. Rémy Martin may be almost 300 years old, but it likes to shake things up a bit. Madame Trichet was only content to retire when she was absolutely satisfied that her protégé had fully appreciated and mastered the house style. For his part, Loiseau modestly admits that he still calls on her for advice if he needs it. She still visits, tastes and offers her thoughts. But this is his moment.

Carte Blanche is so named because the cellar master has total freedom to select it, apparently without interference or any commercial pressure from on high. It carries the Baptiste Loiseau name – even though the original blending was the work of at least two predecessors – because the decision on which of the cellar’s oak-barrelled treasures to release rests solely with him. It’s quite a responsibility. With only 9,650 bottles released, each with an RRP of £350, Carte Blanche is intended to showcase the ‘quintessence of Rémy Martin’, at once capturing the house style – using only eau-de-vie made with grapes from Grande Champagne and Petite Champagne – whilst also delivering something a little different. It’s the second special edition that Loiseau has released, after Carte Blanche Gensac-la-Pallue two years ago.

So how does it taste? The short answer is incredible. The nose, a barrel full of aromas, includes cinnamon, ginger, honey, ripe apricot, orange zest and mirabelle plum. The palate is rich, spicy and complex, yet somehow pure, and the finish is a never-ending story of posh gingerbread men. It’s wonderful when you think that this limited-edition treat is really the result of a cellar master’s inventory. For this ‘stocktake’, Loiseau samples all the barrels, chooses a blend that’s at its peak, and then bottles it.

With ageing in oak comes evaporation, of course – it’s estimated the Cognac business loses more than a tenth of its output to the so-called ‘Angels’ share’ – and those divine beings must have had some wonderful nights at the austere-looking Merpins cellar complex. With the architecture, and high security of a wartime military base, it is home to millions of euros worth of ageing Cognac. Cool, but not damp, subtle spices infuse the slightly stale air.

Oddly, the French don’t really ‘do’ Cognac – only a mere 2% of production is consumed at home. America has the lion’s share, followed by China, then Singapore and Britain. The Cognac industry suffers more than most from the tyranny of the world’s economic cycles, but it is currently in rude health, with annual growth at 10%, driven by the high-value premium market. As one of the first spirits used when the cocktail was created, it’s fitting that much of the current growth is fuelled by its resurgence in that category.

Even the sleepy little town of Cognac itself now boasts a couple of cool cocktail bars (‘Louise’ at the Hotel Francois Premier is a must). So could the future of Cognac be ‘old fashioned’? (For my money, Cognac beats Bourbon in the mix). Loiseau is no purist; he’s fully behind the cocktail boom – and even loves his VSOP served with ginger ale – but won’t be mixing his Carte Blanche with anything: “this must be drunk neat, as the hero is the blend”. And he would know.

Reinventing the traditional: an evening with Martell

Jürgen Schmücking takes Martell by the antlers and is quite taken by a deer called Frédéric and L’OR de Jean Martell, which is blended from 400 component base distillates.

Some call him Frédéric – despite his mighty antlers, Frédéric is a shy guy. Deer like Frédéric roam the parks of Château de Chanteloup, an estate owned by Martell. “Deer in Cognac”, so to say. Sorry, Frédéric.

We visited Château de Chanteloup during our trip to Cognac, as well as some other outstanding producers. Martell brings people to the Château who are important for the house. This includes mainly business partners and importers from all over the world, and sometimes journalists. The dinner was extraordinary as were the paired wines. The Château, the dinner and Frédéric. All this was just the preamble for one of the highlights of our trip – L’OR de Jean Martell. A blend of over 400 extremely rare and outstanding eaux-de-vie from the Borderies and Grande Champagne, L’OR is something like the quintessence of Martell. Liquid history in its purest state. Exotic woods, candied fruit and a potpourri of nuts on the nose, followed by a finish that seems to stay forever.

Hours before, we had the chance to taste the bedrock, the basis for this extraordinary spirit. The smooth and oaky VSOP Médallion, the complex and full-bodied Cordon Bleu, Martell’s flagship on international markets and finally the XO itself. A powerful and spicy symbol for tradition and the great terroir of the Borderies and the Grande Champagne.

Martell has solid roots in history. The spirit of this history is present in each bottle, in the collection of rare vintages and in the way Martell talks about its Cognacs. But there is also a lot of power and energy to shape the future. Ingenuity and innovation lead to products like the extremely fresh Martell NCF, a non-chill-filtered Cognac (the first on the market) or the VSOP aged in red barrels. Pioneering means not only to be stuck in history. It also means reinventing a brand over and over. In short: Martell is back.

Small is beautiful: a taste of Delamain

Charlotte van Zummeren finds that small can be beautiful at Delamain, the seventh smallest Cognac producer.

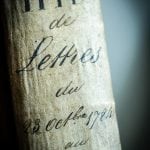

One of the pearls of Cognac is Jarnac-based Delamain. The firm was founded in 1962, with Charles Braastad now serving as the managing director. He is the grandson of Miss Frances Delamain and was raised in the Cognac region. After completing the Business Studies program at Poitiers University, Braastad worked for two years in Scotland. Therefore, he is very knowledgeable about whisky. In 1996, Charles joined his father, Alain Braastad-Delamain and his cousin, Patrick Peyrelongue, to work for the family Cognac company.

Charles Braastad received our press group in the original office, which looks like a museum but is used by employees every day. Delamain is the seventh smallest Cognac house. People who know Cognac know Delamain as an outstanding brand. Madame Bollinger was a great fan of Delamain, the Cognac house which, like Bollinger with its Special Cuvée, puts most of its effort into its Pale & Dry brand. Bollinger is now a shareholder of Delamain.

Delamain only makes XO Cognac, a Cognac with a minimum ageing requirement of six years. The average age of the Pale & Dry is 25 years. Another artefact of Delamain is the diluting with faibles after the blending. Most do it before the blending. Faible is lower alcohol Cognac with water and the faible is aged in Delamain’s case. The angels’ share, the part that vaporises, is not supplemented. The final blend is 47% diluted with faibles to 40%. Then, the Cognac will have months of rest. Delamain makes some other fancy Cognacs, like Vesper and Tres Venerable, but Pale & Dry is its business card.

Edited by Robert Smyth