Michelle Williams discovers how Yarra Valley growers are actually embracing the challenge posed by the dreaded vine root-devouring louse as an opportunity to prepare for another epic cultivation challenge – climate change, as well as using other innovative methods to temper the tiny aphid’s terrible threat.

“Phylloxera is having a significant impact in the Yarra Valley,” laments Sandra de Pury of Yeringberg Winery, “Despite the best efforts of wineries and organizations to contain it, the louse is now found in the majority of the region.”

Home to some of the strictest biosecurity procedures in the world, Australia tirelessly strives to keep its island secure from outside pests, disease, and biological agents—investing $200 million on surveillance and analysis of potential biosecurity import threats. Despite vigilant safeguards, phylloxera reared its ugly head in the Yarra Valley in 2006. While most would succumb to anger and fear, the Aussie ‘can-do’ optimism permeates the region, winemakers chose to use the infestation as an opportunity to make necessary adjustments for another looming threat—climate change.

Phylloxera discovery in the Yarra Valley

Viticulture in Australia’s Yarra Valley, located an hour outside Melbourne in southeastern Victoria, dates back to Yering Station in 1838. As part of the global outbreak in the 19th century, phylloxera was discovered in the northeast region of Victoria, but there is no documentation to suggest its presence in the southeast until its discovery in a vineyard owned by Treasury Wine Estate, following a severe frost in the spring of 2006.

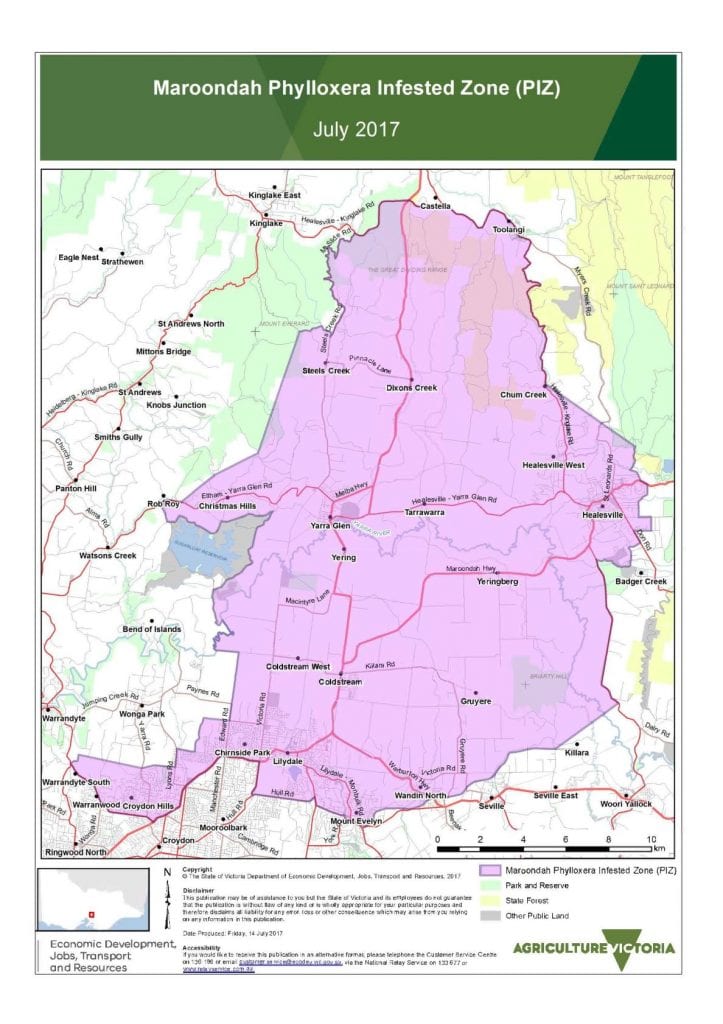

“When a section of vines failed to recover, a dig was undertaken to determine root health, revealing a clear phylloxera infestation, explains Caroline Evans, Chief Executive Officer of the Yarra Valley Wine Growers Association. Best guess today is about 50 vineyards, close to 2,500 acres, are infested, including those replanted on resistant rootstock and those removed since 2006. “I know it sounds strange that we don’t have good numbers, but they change constantly as new discoveries are made. Vines are pulled, some are replanted, but discoveries are not required to be reported if they are within the Maroodah Pylloxera Infested Zone (a 3.10-mile buffer zone created around infected vineyards for containment, there are currently six in Victoria),” she adds.

Lemons into lemonade

Wine regions fear few things more than phylloxera. The hard to detect microscopic louse marches through vineyards with a scorched earth policy, destroying every vine in its path. There is no treatment – the removal of infected vineyards and replanting on resistant rootstock is the costly but lone option.

Cussing, crying, and gnashing of teeth comprise typical reactions to infestation discoveries. While likely the initial response, Yarra Valley winemakers quickly shifted to a ‘lemons into lemonade’ attitude, embracing the opportunity for re-evaluation of past viticultural decisions with an eye to future preparedness.

Winemaker Mac Forbes, of the Mac Forbes Winery, discovered the louse in a “stressed circle of growth” in his Gruyere vineyard in 2013. Challenging viticultural limits through innovative trials, he hopes to find an alternative solution to vine removal by experimenting with attaching resistant rootstocks onto own-rooted vines. “The cost of pulling vines and replanting is both expensive in time and money, but even more of a loss is the older vines that have adapted beautifully to the sites,” he shares.

Many regional wineries, such as Giant Steps, Yarra Yering, Denton Wines, Bird on a Wire, and Payten and Jones share plans to make the best of the infestation by reconsidering planting density, vineyard aspect, row orientation, clones and varieties utilized, trellis design, and more, all to improve vineyard and fruit quality for the future.

Infestations move relatively slowly, allowing viticulturalists time to plan a response. However, once discovered in a vineyard, there likely exists more than is known, creating a sense of urgency in containment and eradication.

Robert Sutherland has been a member of the Yarra Valley Wine Growers Association technical sub-committee since 2006, while he’s also the viticulturist for De Bortoli Wines, the largest wine grower in the region, with over 593 acres. He discovered an infestation in 2013, and began replanting in 2015. “There are still some own-rooted vines on the property that are healthy and productive, but they likely have only a season or two left – once the insect gets going in a block the damage can spread exponentially. It moves faster than many think, and certainly faster than the Victorian government biosecurity department can draw another 3.10-mile circle around a newly discovered infested vineyard,” he explains.

Although Yeringberg has not discovered the louse, they are assuming its presence and began implementing a replanting program a few years ago. De Pury sees the threat as a gradual evolution, “presenting the region with a unique, albeit forced, opportunity to learn from planting mistakes made in the past, and adjust for a changing climate.”

Phylloxera and climate change: looking ahead

As they tackle phylloxera, climate change is also on the minds of Yarra Valley winemakers. “The pest’s presence is a big part of every vineyard’s forward planning,” suggests Stuart Proud, viticulturist and winemaker of Thousand Candles Winery. “We are learning from previous experiences plus trying to prepare for the future, especially when it comes to climate change and unpredictable weather,” he says.

Yerinberg has enough virgin land to plant new vines without removing older ones before necessary. “We are taking the opportunity to plant on cooler, more easterly-facing parts of our hill to combat climate change,” explains de Pury. They are grafting cuttings from their oldest vines onto resistant rootstocks to ensure longevity.

With the warming climate in mind, Forbes is replanting sites previously suited to Pinot Noir and Chardonnay to varieties such as Nebbiolo, Mencia, Grenache, Aligote, and Trousseau. He knows not all these varieties are suited to the sites today, but hopes “some may be a gift to the next generation.” Sutherland also holds future generations in his decisions. “I am making the best vineyards I can for the next person who farms them after me, so even though phylloxera is devastating for many growers, it is possibly the most interesting time that I will ever be involved in over my working life.”

The bigger threat

With both phylloxera and climate posing high threats for devastation and loss, it’s understandable that Yarra Valley wine growers do not have a consensus as to which is the bigger threat. Although the solution to infestation carries a high cost, it is also direct—replant vineyards to resistant rootstock. Because of this, de Pury feels climate change poses a more ominous threat.

By contrast, Sutherland believes the region is more concerned about phylloxera, offering a dim outlook. “Many older growers won’t replant, the wine industry in the Yarra is in a period of decline, there are many moth-balled vineyards.”

While leaning toward the louse, Forbes asks, “Can I flip a coin?” Recognizing the region is home to some cooler sites that are coping well with seasonal variation, his immediate concern is the loss of older vines—the attributes they impart in wine cannot be replaced by younger vines.

“I think both are of equal concern, but at least phylloxera can be controlled to a certain extent,” expresses Proud, “Climate change is such a big issue and much more complex to handle. After the recent summer of bushfires in Australia, I hope people realize how bad things could get if we don’t all do our bit to slow it down.”

Photos taken by Michelle Williams