Michèle Shah climbs the Caucuses, then rocks the cradle of wine, counts the Qvevri and comes back with the oldest winemaking place of all very much on her mind.

Georgia is often called an emerging wine region, but it’s only emerging in our consciousness. It is, in fact, ‘the cradle of wine’, with the oldest viticultural tradition in the world. It’s not surprising that some of the world’s oldest archaeological findings of winemaking, dating back to 6,000 BC, have been uncovered in Georgia – proof of an unbroken winemaking heritage of 8,000 years. More recently, Georgian wine has also been flowing plentifully for Georgians, Russians (with the exception of Russia’s important ban from 2006-2013), Ukrainians, Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians for decades.

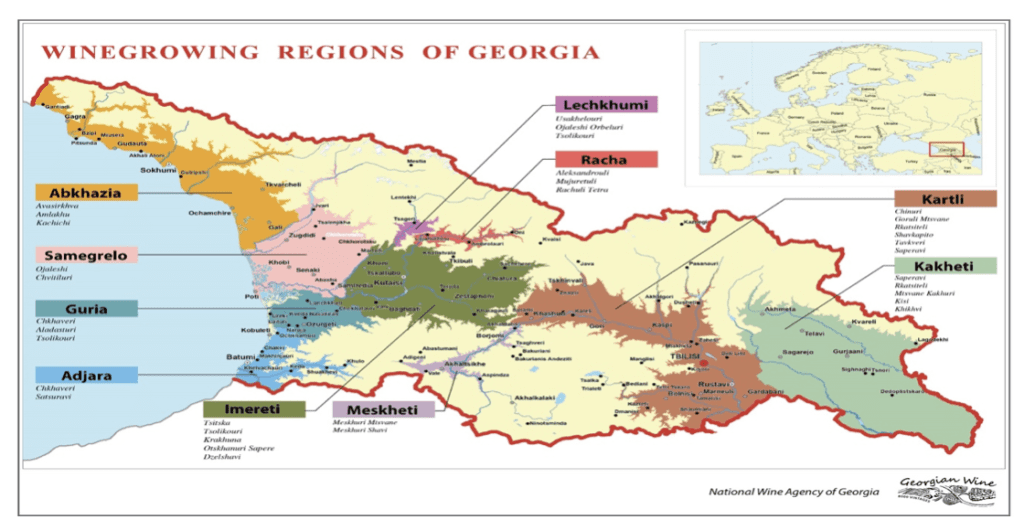

Dominated and protected by the impressive Greater and Lesser Caucasus Mountain Range at the intersection of Europe and Asia, Georgia boasts huge climatic diversity, with areas near the moderating Black Sea characterized by a milder continental climate. At a glance, Georgia boasts some 525 indigenous grape varieties, out of these today 45 grape varieties are currently used in commercial viticulture; 10 regions: Kakheti, Kartli, Imereti, Meskheti, Racha, Lechkhumi, Adjara, Guria, Samegrelo, Abkhazia and 27 PDOs (Protected Designations of Origin). Out of 1,900 registered wineries, 441 wineries export 107 million bottles. The main export markets are Russia, Ukraine, Poland, China and Belarus.

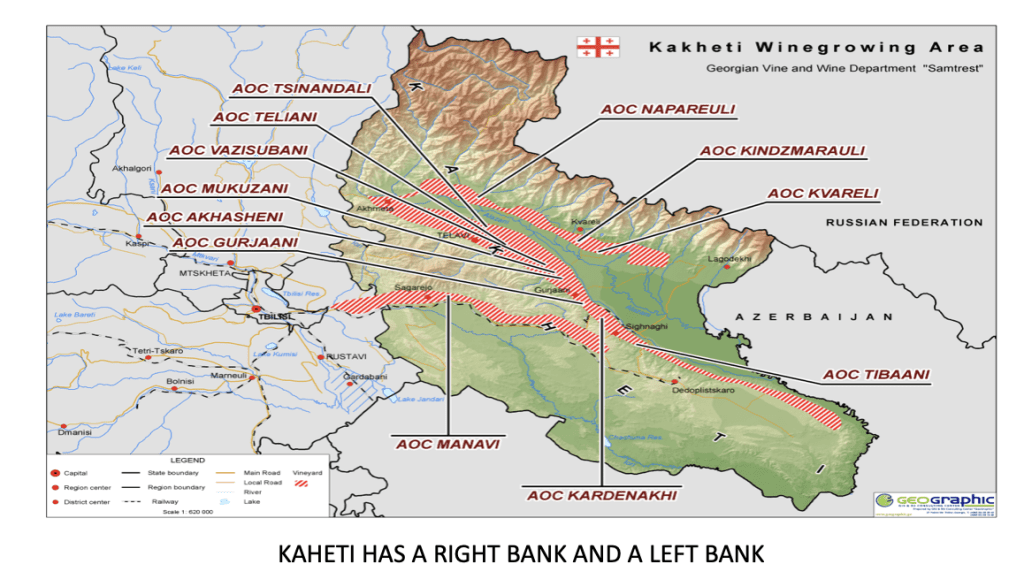

The Kakheti region comprises 44,000 of the country’s total 55,000 hectares (ha), producing 75% of Georgia’s total wine production, from a majority of white varieties, with vineyards planted between an altitude of 250-800 metres above sea level. Production is principally

from three indigenous varieties: white Rkatsiteli, Mtsvane Kakhuri and red Saperavi. However, Kakhetian whites are ever more featuring Kisi and Khikhvi used for still wines, while Chinuri, Krakhuna and Tsolikouri are being used for the emerging sparkling wines.

The Kakheti region is a two-hour drive from Tbilisi (Telavi is the capital of the region) through the leafy, winding Gombori Pass. It is Georgia’s easternmost region, and it shares a border with Russia in the north and Azerbaijan in the south and east.

Supplying the Soviet Union and the rise of Saperavi and Rkatsiteli

In 1921, when Georgia was invaded by the Red Army and annexed by the Soviet Union, it led to the standardization of the once exuberant, individualistic native wine culture. Georgian wine was diminished to the production of industrialized homogeneity, produced in government owned Wine Factory Units – for efficient, reliable supply to the Soviet Union. Since 1991 and Georgia’s full independence, the country’s wine scene has flourished and experience a renaissance, bringing a whole new dimension to its winemaking.

“Georgians planted Saperavi and Rkatsiteli in Soviet times because they grew well and abundantly. We were making four bottles of wine with 1 kg of grapes, but the quality of wine was very poor. In addition, most of the wines were required to be semi-sweet,” says Irakli Mgsloblishvili, head of Shilda’s exports. Shilda is a winery established in 2015, with 70 ha of vines planted in the Kakehti region, producing some 1 million bottles, 7% of which are made in Qvevri.

To cool or not to cool, and other Qvevri questions

The Shilda winery has 24 Qvevries, with a total capacity 48,000 litres, and is one of the very few to produce termo – controlled Qvevri wines – achieved by a cold glycol spiral circulating around the Qvevri, lowering the temperature. According to Mgsloblishvili, temperature control in Qvevri allows for a cold soak, as well as allowing fermentation to be carried out at lower temperatures, making for more aromatic wines, with fresh acidity.

A different approach is used at the Mildani winery, where consultant winemaker Gorgi Dakishvili (one of the most respected vinicultural gurus in Georgia) is of the opinion that there is no need to use temperature control in Qvevri. “It is the size that makes the difference,” says Dakishvili. “A smaller Qvevri will produce a fruitier, fresher style with less structure and tannins, while a larger Qvevri is more likely to produce a less fruity and more phenolic and structured wine.”

The ancient Georgian traditional Qvevri winemaking method practised throughout Georgia, particularly in village communities, was protected in 2013 by UNESCO, as proof of cultural significance and distinctiveness. Knowledge and experience of Qvevri manufacturing and winemaking are passed down by families, neighbours, friends and relatives, all of whom join in communal harvesting and winemaking activities.

Each winemaking region has its own Qvevri-maker, an art which is now in danger of becoming a dying artisanal trade, where the skill is a family trade passed on from generation to generation. Each vessel is handmade and most are lined with beeswax which helps to waterproof and sterilize the vessel, making winemaking a more hygienic process and the vessels easier to clean after each use, though some prefer the ‘raw’ unlined product. If cleaned and maintained correctly, Qvevri can be used for many hundreds of years. The waiting list to order a Qvevri can be up to two years and they can take up to a few months to make. On completion, a Qvevri is fired up for nine to ten days in an oven at a very high temperature of 1,300°C.

This ancient form of natural refrigeration (temperatures are cooler underground) provides a longer maceration period for grapes on fermenting must for up to an average of six months. The extended maceration period develops and determines the increase in aroma and flavour profiles in Qvevri wines. During this time, lees and solids fall into a section at the base of the vessel, where their contact (and impact) is minimal. At the end of the process, wine is transferred to a freshly cleaned Qvevri or another storage vessel until bottling.

Koncho & Co, which was founded in 1924 under Soviet rule and is one of the oldest wineries in Georgia, was one of the first wineries to privatize and become independent. Its current 180 ha produce some 2.5 million bottles – of which 8% is Qvevri, produced from its older 25-year-old vines. Koncho & Co has a grand total of 57 Qvevris, averaging between 1,000 and 2,000 litres, with each buried three metres below ground. Its Qvevri wines stay seven months on the lees and complete both the alcoholic and malolactic fermentation in Qvevri. “In my opinion, Qvevri wines need to go through malolactic fermentation to ensure a softer texture,” says Nugzar Ksovreli, Koncho & Co’s general manager, who is laying the ground for a new Qvevri cellar, and is looking to increase Koncho & Co’s production of Qvevri wines. New Qvevri are coated with cement, allowing them to breathe while protecting them from seismic movement.

Though currently only 10% of Georgia’s total wine production is made in traditional Qvevri, there is a significant growing trend in many wineries to increase the output of wines made in this ‘trendier’ style. Most commercial and exported wines in Georgia are made in the classic, or conventional style, using stainless steel and wooden barrels of all sizes.

Counting on Qvevri

The small village of Napareuli in Kakheti is home to the Twins Wine House and Wine Museum. Founded in 2005 by Gela and Gia Gamtkitsulashvili, who are identical twin brothers, the tradition of making wine has been passed down from generation to generation. This is one of the few wineries that has a significant chunk of its vineyards organically certified (4 ha out of 15 ha in Twins Wine House’s case). The winery is also looking to increase its organic capacity – a challenge due to the high rainfall that can cause frequent and at times aggressive mildew outbreaks, with the associated use of higher levels of sulphur and copper.

“There are 135 Qvevries in our winery. The smallest of these is 50 litres, and the largest reaches 5 tonnes. On average Qvevri range from 400 to 2,000 litres, with a thickness that can vary between ½ cm to 7cm,” says GM Vako Gamtkitsulashvili. He goes on to explain that Twins Wine House was among the first Georgian producers in the history of modern winemaking in Georgia to bottle Qvevri wine. Unlike the vast majority of Georgian wineries, their total production of 250,000 bottles derives only from Qvevri production, using solely wild yeast, producing a range of elegant and softly textured wines with a dynamic energy and distinct character of their own.

Georgian bubbles

Sparkling wines, a growing trend in Georgian production, are considered a tradition deriving more from the western side of Georgia, produced from varieties such as Chinuri, Krakhuna and Tsolikouri, until recently prevalently grown in Western Georgia, but gradually making their way into the Kakhetian production of sparkling wines. Both the traditional method and the Charmat or tank method are increasing production throughout Georgia. The Mildiani winery is currently experimenting with native Georgian grapes to produce sparkling wines, but already produces a complex one from the Kakhuri Mtsovane variety, which spends five years on the lees, and is characterized by acidity and good aromatic quality.

From boutique to big and back again

Levan Chychynadze’s boutique, 35,000 bottle Tiko estate, in Kakheti, is one of the few with homogenous branding, whereby only the label changes colour, making for clear, attractive packaging. His eclectic range includes a yeasty petnat and elegant, barrel-fermented wines. His winemaking experience in Australia and the US has influenced his skills in producing crisp wines of elegance and freshness, particularly identifiable in the Khikhvi grape, which is barrel fermented in a classic Burgundian style, produced from 65-year-old vines found in the Akmetha region of Kakheti. Chychynadze is also a partner in the small, 28,000 bottle Nekresi estate, which exports most of its production.

Kakheti’s Tsinindali region is home to the Tsinandali Estate, which is annexed to the superb Radisson Tsinandali luxury spa hotel. This is where Georgian wine was bottled for the very first time. The establishment of the Tsinandali estate is connected to Prince Alexander Chavchavadze. Going back to the 19th century, in addition to being an excellent winemaker, he was a businessman, a military man, a poet, and one of the pioneers of Georgian romanticism.

“Georgian winemaking is a paradox,” says Kolka Archvadzde, commercial director of Tsinandali Estate. “We are the oldest wine-producing country, yet we are one of the youngest. If you go to Tblisi its difficult to find a wine older than vintage 2007.”

At the other end of the spectrum, Marani Casreli (Marani means winery) is a small ‘garage’ winery in Vachadziani village in the Kakheti region, established in 2015 by a group of doctors, whose love for wine led them to initially plant a single-hectare vineyard. Their current 8 ha vineyard, managed by Dr Misha Doudze, produces some 15,000 bottles of ‘natural’ Qvevri wine, which is characterized by an authentic, soul driven style. Doudze is the perfect Georgian host with a contagious smile and who exudes joie de vivre.

His warm hospitality and delicious home-made dishes accompanied a fine line-up of wines – followed at the end of the meal by the obligatory shot of Chacha. This is similar to a grappa or an aquavit, made with the leftover skins, stalks, and pips. “Nobody really knows how Qvevri wines age, as they are always drunk young,” says Doudze, with a large grin and twinkle in the eye.

“They could out-eat us, out-drink us, out-dance us. They had the fierce gaiety of the Italians, and the physical energy of the Burgundians. Everything they did was done with flair…nothing can break the individuality of their spirit.” John Steinbeck, on Georgia and Georgians, in ‘A Russian Journal’, 1948.