This month our edition is dedicated to the Circle’s trip to Cyprus, which took place in late April 2025, following fairly hot on the heels from last year’s February visit to this exciting Mediterranean wine island. We hand over to members to report on their highlights of the trip, which took in an entirely different set of wineries to the 2024 tour.

…

After describing the delightfully dramatic descent while coming into land in Larnaca, Leona de Pasquale continues to set the Cypriot scene and then gets the visits underway at Mallia winery.

As my flight from London descends into Larnaca Airport on Cyprus’s southern coast, the view is striking: undulating hills, a winding coastline and white streaks across the terrain, shaped by underlying limestone, like brushstrokes on a green and brown backdrop. It’s breathtaking, though not quite the palm-fringed scene I had imagined.

From our base in Paphos, on the island’s western side, we travelled to Limassol for our first visit: Mallia Winery, owned by the long-established Keo Group. Beyond the scenery, the drive revealed Cyprus’ layered heritage, brought vividly to life by our tour guide, Ulla Ignatiou Margareta. We passed ancient olive trees and carob groves, the latter yielding what are locally nicknamed as ‘black gold’. Mount Olympus rose in the distance, flanked by the rugged Troodos Mountains.

As the third-largest island in the Mediterranean after Sicily and Sardinia, Cyprus enjoys more than 340 days of sunshine a year and carries significant geopolitical weight. Situated at the crossroads of Europe, Asia and Africa, it has long been a strategic prize, contested over the centuries by Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Ottomans and the British. Even today, its division since 1974 into Greek and Turkish zones reflects wider regional tensions.

Mallia Winery, perched at 1,000 metres above sea level, greeted us with crisp air and sweeping mountain views. We were welcomed by oenologist Matheos Christofi, brand manager Yiannis Fatseas and agronomist Timos Boyas, and were later joined by Dimitris Antoniou, Mallia’s wine manager and oenologist.

Founded in 1927, Mallia owns more than 50 hectares of vineyards and works with over 1,000 growers from across the island. It’s a proud member of WineCore, a 2021 initiative by the Cyprus Wine Consortium uniting 14 leading wineries committed to preserving and promoting the country’s indigenous grape varieties through quality-focused winemaking. Mallia produces estate wines from native grapes such as Maratheftiko, Yiannoudi and Xynisteri. It also vinifies international varieties like Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot – though only from its own vineyards.

While Cyprus is no stranger to scorching summers, water scarcity has become one of the island’s most pressing challenges. At Mallia, the impact of climate change is increasingly visible. Yields have declined significantly, with harvest volumes dropping from the usual 3.5 million kilos to just 1.7 million in 2024 due to heat and drought. To protect fruit quality during harvest, when temperatures often soar, the winery uses specialised chillers to cool grapes quickly. White varieties, such as Xynisteri, can arrive from the vineyards at 30°C to 40°C and are rapidly brought down to 5°C-10°C to preserve freshness. After a brief settling period, fermentation begins at around 15°C. Red grapes follow a similar path, fermenting slightly warmer to develop structure and depth.

As one of the island’s largest wineries, Mallia also operates a cellar in the nearby village of Arsos, as well as a facility near Franklin Roosevelt Avenue in Limassol, where beer is brewed and Commandaria – Cyprus’s historic fortified sweet wine – is aged and bottled.

Before leaving, I asked Dimitris Antoniou about the future of Cypriot wine. Despite the climate challenges, he remains confident. “Cyprus is well prepared for the new world of wine,” he said. “We’re used to heat and adapting to changing conditions.” He is especially encouraged by the return of young professionals. “We have a lot of good young winemakers who have come back to Cyprus. We all work together to promote our indigenous varieties.”

As for the future of the native grapes, Antoniou sees strong potential in both Yiannoudi and Maratheftiko, but views Commandaria as the true identity of Cypriot wine. When I asked whether the difficult grape names might hinder international appeal, Antoniou acknowledged the challenge but stood by their uniqueness. “Maratheftiko and Xynisteri aren’t easy to say. I know people prefer simpler names. But niche markets will love these varieties. In fact, I don’t like it when people use international grapes to draw comparisons with ours. I want their unique character to shine, because they’re one of a kind,” he concluded.

My top three wines from Mallia Winery:

Xynisteri 2024, Limassol Regional Wine

Soft and rounded, with bright acidity and notes of white peach, apricot and melon. A subtle saline finish brings coastal freshness.

Heritage Maratheftiko 2021, Limassol Regional Wine

From 30-year-old vines. Garnet hue. Aromas of violets, wild herbs and red plum. Supple tannins support flavours of sour cherry and cranberry. Poised and elegant.

Yiannoudi 2023, Limassol Regional Wine

First vintage. Deep ruby. Blackberry, redcurrant and dark cherry over chalky tannins. Refined structure and a lifted, persistent finish.

…

After the first visit, our group has built up a considerable appetite. Next up, Bart de Vries tucks in to lunch at Tavernaki tis Lenias and hands a maximum 12 points to Cyprus.

While Cyprus did not make it to the final of this year’s edition of the Eurovision Song Contest, which was held in my hometown of Basel, I was still basking in the afterglow of a fabulous press trip to the island of Aphrodite. Indeed, when it comes to wine and rural scenery, Cyprus definitely deserves the full 12 points, and not just from Greece!

Cyprus’ main white grape variety, Xynisteri, is capable of some really beautiful, fresh, semi-aromatic wines that pair wonderfully with the local dishes we tried over a lunch at the charming taverna Tavernaki tis Lenias (Lenia’s Tavern) in the pretty village of Vouni, high up in the stunning Troodos mountains. Navigating the steep, cobblestoned streets towards the restaurant, we passed a typical kafeneion (coffeehouse) with a large, old tree shading the terrace decked with blue tables and matching matted chairs, from where an old man, walking stick in hand, was just making his way back home.

Lunch started with the ubiquitous, but no less delicious Greek (or should I say Cypriot?) salad, a velvety tahini (a sesame dip), tzatziki, olives and warm, fluffy pita bread. Yes, Greece and Cyprus, are culturally very close neighbours. The meal continued with a number of mezzes, among which grilled haloumi with slices of pork loin, battered and crispy deep-fried aubergine slices, sheftalia (pork and lamb sausage) and fried ground courgette balls with bulgur. Yes, the Middle East isn’t far either.

Since we know that Israel, alongside Georgia, was the cradle of winegrowing (Economist, March 2023), it is hardly surprising that Cyprus has an ancient wine culture. The flight to Tel Aviv is only 40 minutes and, as the crow flies, Beirut is even closer.

Our lovely mezzes, traditionally made from leftovers for unexpected guests, were washed down with two fantastic dry Xynisteris. My favourite was the one from Vasilikon, a female- led winery from the Paphos IGP. Lemony with a waft of tropical fruit, finely textured, slightly leesy, lively and rather long, it was thirst-quenching and perfectly accompanying the mezzes. Tsiakkas’ interpretation of the same variety may be a tad broader, but every bit as good. Cyprus is rich in limestone, and with the grapes being grown at considerable altitude – Tsiakkas’s label rightly carries the epithet Heroic Viticulture – the wines are, despite the island’s latitude, wonderfully crisp and fresh. Vouni and Lenia’s, but also Vasilikon and Tsiakkas: douze points!

…

At LOEL winery, on the hillside above Limassol, Sue Tolson sips her way through Zivana and single-varietals of white Xynisteri, rosé Lefkada and red Maratheftiko, before covering Commandaria, the ‘modern history’ of which began with the Knights Templar.

LOEL Winery’s new state-of-the-art production facility, built in 2019, is located on the hillside above Limassol. This huge facility was our destination on the first afternoon. Situated in a less-than-scenic location in an industrial area, the large, corrugated metal building houses some seriously large stainless steel tanks. So, it was no surprise to learn that this winery, established in 1943 and the first public limited company in Cyprus with thousands of shareholders, mostly viticulturists, is one of the largest wineries in Cyprus.

Although its main business is Zivana – Cyprus’ answer to grappa, producing a staggering 500,000 litres each year and making it the market leader with an 85% share of the market, it also produces wine on a similarly impressive scale. They make 500,000 bottles of entry-level wine, 100,000 bottles of mid-price wine and 50,000 bottles of premium wine each year. In addition to that, they are also unsurprisingly one of the biggest Commandaria producers, bottling 50-60,000 litres of the sweet, fortified wine, and the ambassador to Cyprus’ age-old wine culture. Moreover, they also pioneered the production of quality wines in Tetrapak on the island, under the name Vinotheque, which have proved highly successful both in the local market and abroad.

With such a huge demand for grapes (they need 5 million kilos of grapes for Zivana alone!), they have also now planted their own vineyards, in the wine-growing areas of Limassol and Paphos. These plantings include Cypriot, Greek and international varieties, such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah and Sauvignon Blanc. As these vineyards are not yet productive, they still buy in around 5.5 million kilos of grapes from growers, especially in the Paphos area.

Even though they are a massive company, exporting to many countries including Greece, England, America and Estonia, they are keen to show their Cypriot roots, thus the labels of their mid-price Morfes single-varietal range, featuring a white Xynisteri, rosé Lefkada and red Maratheftiko, are adorned with pictures of animals commonly found in Cyprus. The premium range ‘Evamelos GH’ comprises only red varieties and consists of Maratheftiko, a Cabernet Sauvignon/Syrah blend and Cabernet Sauvignon.

The Zivana range has also recently been expanded to include a Zivana GOLD, which is oak aged with a touch of honey, lending it a lovely smokiness and smoothness on the finish, as well as a Zivana RED, which is enriched with cinnamon.

Commandaria, the traditional Cypriot fortified wine made from indigenous varieties Mavro and/or Xynisteri with a history dating back to the late 12th century, is produced in two versions at LOEL. Commandaria Alasia Classic and Commandaria Alasia Vintage. We tasted the Vintage 2005, which had picked up a gold medal at IWSC – a symphony of coffee, hazelnut, dried fig and walnut. They also make coffee, juices, confectionery and snacks!

The cultural heritage of Commandaria

Given the importance of Commandaria to the island’s vinous history and the fact that it celebrated its 800-year anniversary last year, we were privileged to meet Thoukis Georgiou, the Cypriot state oenologist, before we sat down to our tasting of LEOL wines in the presence of the enormous stainless steel tanks. Thoukis is now the vice president of the OIV Culture, Education and Heritage Group and is the first Cypriot elected to the OIV in the last hundred years, so he was delighted to present to us about Cyprus’ legendary wine product Commandaria and its illustrious history. He believes that it is part of the country’s heritage and can be a vehicle of wine diplomacy, opening doors and promoting Cyprus, not only in terms of tourism, but also as a destination for culture, walking and wine.

Its modern history began with the Knights Templar, who ruled the island from 1192 and were tasked with the protection of Christian sites, including the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. However, the ancient Cypriots had produced a similar wine from sun-dried grapes under various names including ‘Nama’, with mention of the sun-drying of grapes as early as 8 BC. Nevertheless, it gained its current name under the Knights Templar thanks to their three Commandarie on the island. It was widely exported to medieval courts during Venetian rule, so was famed Europe-wide, even during the Middle Ages. During the 300-year rule of the island by the Ottomans, the volume of production and consumption declined, thanks in part to the taxes they levied on it, as they had rightly understood it was a precious product to be commercialised – although that seems to have backfired.

It was only with the arrival of the British that the Commandaria tradition was revived, with the British administration starting the tradition of fortification in 1878, similarly to other wines exported to Britain, such as Sherry, Madeira, Port and Marsala.

Nowadays, Commandaria is a PDO, with only 14 wine villages permitted to produce it, on around 420 ha of 7,000 ha in total in Cyprus. It may only be produced from the two most common local varieties – Xynisteri and Mavro, either together or alone. Grapes must have at least 374 g/l of natural sugars with a potential alcoholic strength of at least 22%. They are then sun-dried for 10-20 days, depending on style, before undergoing a long, slow fermentation and must spend at least two years ageing in oak. It may or may not be fortified, although fortified styles are currently 95% of the market, with smaller, boutique producers often eschewing the fortification. The alcohol will tell you which version it is, as this is not necessarily on the label – over 15% abv and it’s fortified, with non-fortified versions usually sitting around 12-14% abv.

As a sweet wine, it could be promoted solely as a dessert wine, but Thoukis doesn’t agree, believing that for the Cypriots, it is a lifestyle wine that can be enjoyed as an aperitif, during the meal or as a digestive. It’s so important to the Cypriots that they’ve applied for its inscription as part of UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

…

APRIL 25

…

Adam Montefiore climbs up high to the Santa Irena Winery and marvels at meeting Daniel Anastasis, who coaxes wine out of the clouds.

I was delighted to be included in the Circle of Wine Writers visit to Cyprus. It is a fascinating wine country. Paradoxically, the renaissance of Cypriot wine is occurring right now, yet it is one of the oldest wine-producing countries. Cyprus seems less part of Europe’s Old World of winemaking, and more realistically fits in to the ancient world of the Eastern Mediterranean, the cradle of wine culture. Cyprus to me means high altitudes, mountainous vineyards, indigenous varieties and an unusually high percentage of old vines. These qualities were certainly symbolised on our visit to Saint Irena Winery.

To arrive at the winery we had to drive slowly in wavy zigzags, climbing steadily, whilst enjoying dreamy views, overlooking steep drops, with the ground alternatively covered with limestone stones or volcanic rocks. There were vines everywhere, most grown in the bush, goblet style. They were often in terraced mosaics of small lots of family-sized vineyards, all at different aspects, each spouting gnarled old vines, with wild, flailing branches, like waving arms on a sinking ship. We climbed to over 1,000 metres above sea level until we arrived at a small village of only 500 inhabitants, called Farmakas, which is in the Pitsilia region, part of the Nicosia district.

The wine grape of the area has always been Mavro, which means black. This is the most planted variety in Cyprus and is the workhorse grape of the island. What is not in its favour is that it produces large grapes, is thin-skinned with a poor colour and it can be light in taste. What is for it is that it is versatile and there are many old-vine vineyards. The growers in Farmakas are getting older and sadly, but perhaps inevitably, the next generation prefers to work in the hi-tech sphere and live in cities, rather than endure the struggles of everyday agriculture. Therefore family agriculture over generations is gradually drying up, leaving the vines to cope alone.

Daniel Anastasis, a son of Farmakas, remembers those same vineyards and grower families as a child. He used to be commandeered to work in the vineyards after school. He remembers his grandfather making wine in the large pithari clay jars, which today decorate every winery and the garden of every home; also the donkeys, the farmers’ best friends, used in the vineyards and during the harvest. However, circumstance and opportunity took him overseas, first to Australia, and then to South Africa, where he made his name as a master baker. When he returned in 2010 at 65 years old, he was at an age when most people would be considering retirement. However, he was confronted with a forlorn sight. The high elevation vineyards (up to 1,300 metres above sea level) were still there, as were the old vines, ranging from 100 to 130 years old; but some were not worked anymore and in others the ageing farmers did not have the resources or energy to manage the vineyards in the future. There is nothing so desperately sad as an abandoned old-vine vineyard.

So Daniel felt pangs of nostalgia for his childhood and thought he owed it to his grandfather to do something. He understood the potential of those old vineyards shorn of respect and lacking care and attention. He bought a few plots and cajoled some of his neighbours to contribute others. The vineyard owners were supportive, only too happy that someone would look after their life’s work. In 2016, he founded Santa Irene Winery, named after the local church. His objective was to coax and encourage the ancient but much maligned Mavro vines to produce wines of quality. This was at a time when most quality-oriented wineries, who were bristling with gleaming New World technology and internationally trained winemakers, had long abandoned the neglected Mavro, preferring either the local Maratheftiko and Yiannoudi, or international varieties like Shiraz and Cabernet Sauvignon.

The heart of his search for quality Mavro lay in what he called the Vinea Ardua, which means arduous vine in Latin. These special vineyards, ranging from 900 to 1,200 metres in elevation, were first harvested in 2020. The slopes are genuinely steep, in some cases reaching 60 degrees. They are not new vineyards planted for ease of managing vineyards, but ancient vines that have clung onto the slopes of the Troodos Mountains, as though hanging on for dear life. Daniel bought in expert viticulturists and trained winemakers. These vines were damaged through neglect and needed extraordinary patience and TLC to bring them back to produce quality fruit. At the same time, all vineyard work was extremely difficult and hard physically. To cap it all off, yields were painfully low.

The winery has invested in small state-of-the-art stainless tanks to aid bringing winemaking into the 21st century and they also have a beautiful still for making Zivania. However, this did not satisfy Anastasias. He scoured the village for old pithari and refurbished them, bringing them back into use for fermentation. For punching down, he uses a shepherd’s staff, which he brandishes almost like a weapon, waving it about and using it as a pointer during the presentation he gave us.

Daniel Anastasias is now 80 years old, but still full of energy. He is a performer who relishes an audience. He comes alive in front of us telling stories and reminiscing, occasionally pausing mid-story to bark instructions at his employees, before returning with the punchline. Much of his 50,000 bottle production he sells on site. He has created a haven for wine tourism, with a large restaurant area capable of coping with tourists. He also owns a bed and breakfast facility in the village.

The winery produces its value wines under the Santa Irene label, but the crème de la crème are under the Vinea Ardua label. The vines are grown organically. They use natural yeasts, minimum sulphuring and light or no filtration. His leading three wines are named Eteon (meaning genuine), Aepys (steep) and Aeoneo (eternal.) The Eteon is a white made from Xynisteri. There are tiny plots of this white variety within the Mavro vineyards, sometimes to the point of being single white varieties in a sea of red. These are carefully picked, part fermented in pithari and part in stainless steel. Xynisteri can produce very ordinary wines in low altitude vineyards, but here touching the clouds the result is different. We were served the Eteon 2021, but I would have preferred a more recent vintage.

We also tasted a Blanc de Noir called Danero 2022, and a flavourful rose called Erroa 2022, both made from Mavro of course. The Danero was the one I preferred as it had a satisfying taut texture from head to tail. Of the reds, the Aepys 2021 was treated in a modern way, fermented in stainless steel, then aged in old barrels, but for only six months, so as not to swamp the delicate fruit with wood flavours. The Aeoneo 2021 was more traditional, made in an echo of the long forgotten past. It was fermented in pithari and then aged in second use barrels for six months. I preferred it, out of the two. It had a red nose of red berries and cherries, a medium weight on the palate and a tannic finish that provided a contrast and had a refreshing quality.

Daniel Anastasis is a man who in a second career, at three score and ten, returned to revive agriculture in the mountains surrounding his village. He saved the vineyards from the ignominy of being abandoned, revived winemaking in the ancient way and was determined to make a quality Mavro by focusing on the qualities, rather than bemoaning the variety’s frailties. Only someone on a driven mission would have persevered. Quite apart from that, it is a wonderful place to visit as a tourist, and if wine bores you, you can go and pet the donkeys which he considers part of the family.

…

Tony Harries revels in Revecca’s command of Commandaria.

We continue to tour and witness the exciting regeneration of the Cypriot wine industry, but every innovation needs a point of focus, and following a variety of visits, our minibus takes us to the area where Commandaria rules.

Commandaria, the oldest of named wines, must be made in the small, but mountainous area of 14 traditional villages that history has designated to be Commandaria country, and as we wind our way up through vines clinging to the land tighter than a taxman’s grasp on your money, we’re heading to the small family producer of Revecca in the village of Agios Mamas.

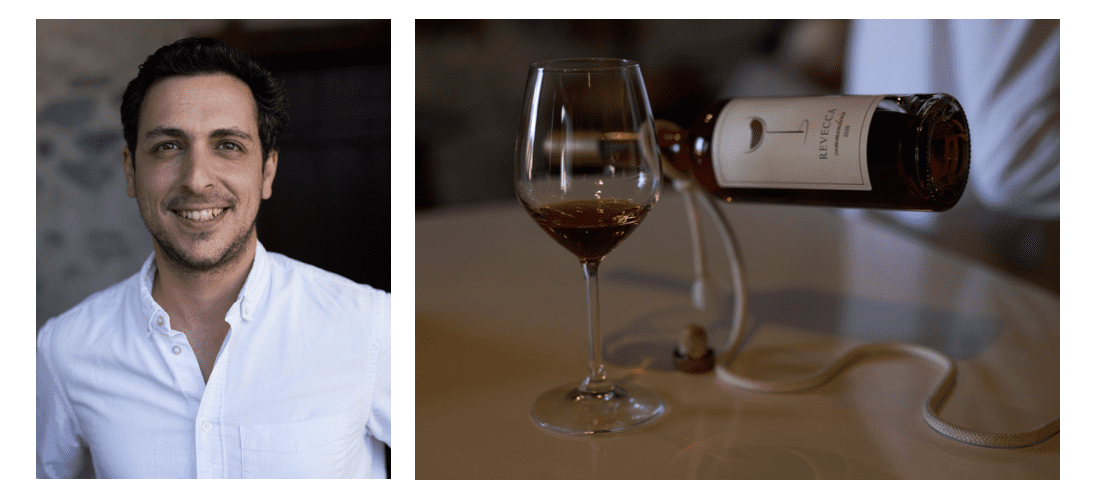

We park, get off the coach, walk up the street, walk down the street because we’ve gone the wrong way, turn down a smaller street, past a couple of benevolent donkeys who stare pitifully at us, before meeting our guide for the tasting. He’s a man called Nikolas who is not only a talented winemaker, he’s also more youthful than some of the suits I own. He leads us round a corner, and we ready ourselves for the wonderful site of vineyards rising up and coating a mountain. What we actually see is a small neon sign, and below it an antiquated doorway through which one gingerly passes through before moving along a courtyard that is so small the swinging of cats cannot take place, should you wish to indulge in such a thing.

Within moments we’re inside and sitting in a taverna that’s doing its best impression of an old Cypriot woman’s house. We later learn that it did actually belong to an old Cypriot woman, the grandmother who gave her name to the winery. The building we’re expectantly sitting in is rented by the current owner who uses it as part tasting room, part museum and part cellar. They’re quietly determined these Cypriot folk when it comes to using space. It’s here that we learn what Revecca is bringing to the Commandaria party.

The grapes they grow come from the ten hectares of vineyards that are spread across the villages of Agios Mamas, Lanela and Doros, and Nikolas tells us that Revecca doesn’t believe in messing with a successful formula, so, it’s no irrigation, grapes are sun-dried in the open (sometimes football pitches have been used for a large harvest) and the use of the pithari, or clay pot. After the sun-drying, there’s basket pressing, and no additions other than sulphites. This allows the four- to 80-year-old Xinisteri and Mavro vines to produce a wine that focuses on the taste profile without allowing the alcohol content to swamp the wine, as can happen when it’s fortified.

Revecca sells the majority of the 10,000 bottles it produces to other wineries but keeps hold of 3-4,000 bottles. The popularity of its wine means that every year Revecca sells out and can be a little choosy about which outlets it chooses to market its wine. Lifting a glass and tasting this evocative Commandaria, you understand the marketing strategy completely. I love this tranquil place, well as tranquil as a place can be with 14 members of the CWW tucked snugly inside.

The wine more than lives up to its billing. I had a notion that I might enjoy a glass. I’ll just tell you that Revecca’s Commandaria has more nuance and elegance than you’d get from a Savile Row tailor. This could really be the point of difference for Cypriot winemaking, the lifestyle sip, the gateway drink that draws you towards their other indigenous varieties, but I’ll leave that for another time as I savour rich, nutty flavours and tastes of dried and candied fruit that bring reminders of Christmas. This is a wine for dreaming of another life, in which you sit playing cards outside a village bar high up in the Troodos mountains as glass after glass is sampled and the merits of Revecca’s delicious wine is talked over, but not for too long, because there should always be time for another glass.

Now, if you bookend this enlightening visit with the first night when Sue Eames and I nearly ended up in a dubious place called ‘The City of Dreams’ and Michele Shah asking me to pass her the pot (some tasty aubergine dish she assures me), I must say that the reputation of Cypriot wines can only grow and grow, and the Commandaria of Revecca will enjoy the recognition it deserves.

…

Per Karlsson reflects on the long history of a family-made Commandaria at Karseras Winery.

Some olive trees in Cyprus are estimated to be over 2,000 years old. That means that even though Commandaria is the oldest named wine type in the world, some of the trees on the island had been growing for more than a thousand years before Commandaria became famous. But even if it is an ancient wine type, until recently, there were only a handful of very large producers making it.

One of the pioneers of “growers’ Commandaria” is the Karseras Winery. It was established as a Commandaria-producing winery in 1998, though the family had been growing grapes long before that. The winery was founded by Panayiotis Karseras, whose son, also named Panayiotis, and grandson, Filippos Karseras, now run the business.

However, even though it is a relatively young winery, it has a long family history. When asked how long his family had been making wine, Filippos replied: “Literally, since forever. The University has told us that the first Karseras in our area was mentioned in the 11th century.” While ‘forever’ may be a stretch, the continuity of family viticulture over centuries is unmistakable. Like many others, the Karseras family had previously made wine for personal consumption, as the commercial market was dominated for much of the 20th century by four large companies. The revival of the Cypriot wine industry in the late 20th century opened the door to smaller, quality-focused producers like Karseras.

The winery is located in Doros (Dhoros) village, around 30 minutes from Limassol, and is one of the 14 villages on the southern slopes of the Troodos Mountains permitted to produce Commandaria. The winery focuses solely on Commandaria, with no commercial-scale table wine production. Their 15 hectares of vineyards are spread across six of the designated Commandaria villages. The principal grape is Mavro (black), with some Xynisteri.

Today, both fortified and non-fortified versions of Commandaria exist. While fortification was historically the norm, smaller producers increasingly favour the non-fortified method. Filippos is a strong advocate of this approach: “When you put spirit in it, you kill everything,” he says. At Karseras, the wine is vinified in stainless steel, aged in barrel, and finally in bottle.

Their Family Edition Commandaria spends two years in barrel and undergoes light filtration before bottling. It typically contains 90 to 95% Mavro, with the remainder Xynisteri. Bottled in a distinctive, short, tubby bottle, it features an original label depicting the founder of the winery, Father Panayiotis Karseras — a local priest who served his community for 60 years. The wine is gently sweet, light in style, and lifted by a refreshing acidity.

For their more premium wine, Platinum, no filtration is used, and the wine is aged for 20 years. The current vintage, 2005, contains 155g/l of residual sugar. Yet it, too, is made in an elegant and refined style, with flavours of sweet apricot marmalade, honey, and spices. A slight natural deposit may occur due to the lack of filtration.

Outside the winery, a row of ancient-looking olive trees stands in quiet witness to this enduring family tradition — trees that were already old when Father Panayiotis was born. A history, quite literally, rooted in the land.

…

APRIL 26

…

Jochen Erler engages with the Ezousa Winery and particularly enjoys the single-vineyard Xynisteri, Giannoudi and Maratheftiko bottlings.

Finally the sun had won over the sand from the Sahara. Instead of a grey sky, we had a beautiful summer-like day. We travelled through a hilly and gentle landscape that was much greener than the mountainous area of the previous two days.

Our first destination of the day was the Ezousa Winery, in the village of Kannaviou, which we reached by following many curvy roads that followed the former mule paths along the contours of the hills. Michalis Constantinides, the owner and winemaker at Ezousa, gave us a hearty welcome and he recognised some from among us. From the village at an altitude of 400 m, we had a good view of a large valley cultivated with fields and vineyards, surrounded by some hills. According to Constantinides, his vines enjoy a high diurnal temperature range and of the cooling influence of a river, allowing him to work organically in his vineyards.

The winery is medium-sized with modern technology, as we had already seen in all the other wineries. The yearly output is 80,000 bottles, produced from 20 ha of vineyards, 12 ha of his own and 8 ha owned by some 200 local farmers. In the tasting room, 17 wines waited to be tasted, not only wines already released, but also two experimental ones. Although the Ezousa winery had followed the trend to plant international varieties like Cabernet Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc, Syrah and Viognier, Constantinides is now putting his focus again on the local grapes, retaining however Syrah and Viognier. Indigenous varieties are normally well suited to dealing with adverse climatic conditions like excessive heat. However, Ezousa’s Viognier and a cuvée of international red varieties are of top quality.

Most of the Ezousa wines come from single vineyards planted some 35 years ago, a time when the four big wineries lost their practical monopoly as commercial wine producers, because many grape growers had started their own wineries. Among Ezousa’s best wines were the single-vineyard Xynisteri and Giannoudi of the 2022 vintage, and Maratheftiko of 2018 and 2020, all potential winners of gold awards at any wine competition. Constantinides’ generous gift to each of us was a bottle of 2018 Maratheftiko that has the potential to live much longer than some of the members of our group.

…

In the village of Letymbou, Luisa Welch serves up a gastronomic interlude, in which our group get to bake bread and are rewarded with a lovely lunch of local delicacies.

Along with a history of winemaking dating back centuries, Cyprus offers a delightful blend of Mediterranean flavours and delicious local dishes, which pair so well with the island’s wines.

On the recent CWW study trip to Cyprus, between visiting wineries, meeting producers and tasting wines, we were treated to a gastronomic interlude when we travelled to the village of Letymbou, just 12 km north of bustling Paphos, although it felt like a whole lifetime away. Nestled in the scenic countryside, this village exudes a serene and timeless atmosphere that captures the essence of traditional Cypriot life.

It’s here that we met one of the most charismatic people I have ever come across: the legendary Sofia, who runs ‘Sofia’s Traditional House’. The epicentre of the village, the ‘house’ is a bakery – Sofia bakes 200 bread loaves to order every day – but it’s also an impromptu cookery school and a restaurant. And it’s home to many cats – cats abound in Cyprus!

Following Sofia’s guidance, we attempted to make bread, some more successfully than others. Oh, but did it taste good when it was baked and was served at the table! Watching halloumi being made was a mesmerising experience. This typical Cypriot cheese is made by first coagulating milk with rennet to separate curds and whey. The curds are then heated in the whey, pressed in a mould and brined in a salted whey solution. This process gives halloumi its characteristic salty taste and the unique, firm texture that holds its shape when cooked.

And so to the table for a rewarding lunch after all this hard work. The dishes just kept on coming, ‘that’ bread, and ‘that’ halloumi sprinkled with mint took centre stage, and then so many dishes it’s almost impossible to list them all. A glass of the white Xynisteri 2024, like the one we tasted at the Tsangarides winery, would be perfect with the cheese. Fresh, citrussy and with good acidity, from a very good year, this Xynisteri undergoes a cold maceration for eight hours thus taking elegant aromas from the skins. Batonnage and three months in oak gives it body and complexity.

And so to the table for a rewarding lunch after all this hard work. The dishes just kept on coming, ‘that’ bread, and ‘that’ halloumi sprinkled with mint took centre stage, and then so many dishes it’s almost impossible to list them all. A glass of the white Xynisteri 2024, like the one we tasted at the Tsangarides winery, would be perfect with the cheese. Fresh, citrussy and with good acidity, from a very good year, this Xynisteri undergoes a cold maceration for eight hours thus taking elegant aromas from the skins. Batonnage and three months in oak gives it body and complexity.

Achieving standout was kleftiko, lamb slow roasted until it’s incredibly tender and falls off the bone. The name ‘kleftiko’ translates as ‘stolen’, referencing the historical practice of bandits stealing lamb and cooking it in underground pits to avoid being caught. This dish, traditionally cooked with herbs, vegetables and potatoes, would be outstanding with a glass of red Aeoneo 2021, from the Santa Irene Winery high up in the mountains. Made from 100% Mavro grapes from vineyards which are over 100 years old, this ripe, rich wine with an intense spicy aromatic bouquet and a tannic full body, would admirably complement the richness of the kleftiko.

Kotopoulo – simple roast chicken, so moist and tender, a refreshing horiatiki – peasant salad with flavoursome tomatoes, olives and feta, where just a delight for all the senses.

When Lukumades were brought to the table, it was time to end the meal in style. This popular Cypriot dessert, like small deep fried doughnuts crispy on the outside and soft on the inside, where deliciously drizzled with local honey and a little sugar. A glass of Commandaria, the wine for which Cyprus is rightly famous for, would be just perfect. Like the artisanal Commandaria tasted at the Revecca Winery, dedicated to preserving the authentic taste and traditions of Commandaria. Made to strict PDO regulations, not fortified and produced in limited quantities. Matured in old barrels and aged for two years, it is sweet yet balanced, with notes of hazelnut and dried fruit, honey and a fresh tangerine finish.

A short coffee and a glass of Zivana, the traditional Cypriot spirit distilled from locally grown grapes and a symbol of the island’s cultural heritage, ended what can only be described as a most unique experience for all the senses. Zivana is protected under EU regulations and can only be made in Cyprus, so it was a real treat to taste it. We waved goodbye to Sofia and her husband Andros, and were on our way to the next tasting.

A short coffee and a glass of Zivana, the traditional Cypriot spirit distilled from locally grown grapes and a symbol of the island’s cultural heritage, ended what can only be described as a most unique experience for all the senses. Zivana is protected under EU regulations and can only be made in Cyprus, so it was a real treat to taste it. We waved goodbye to Sofia and her husband Andros, and were on our way to the next tasting.

…

Anne-Wies van Oosten concludes our Cyprus coverage in the foothills of the Troodos Mountains, at the Tsangarides Winery.

The final winery visit of our trip to Cyprus brings us to Tsangarides Winery in Lemona, in the Paphos region. We thought we had already learned everything about the indigenous grape varieties, but once again, we’re in for a surprise.

The winery lies in the foothills of the Troodos Mountains, a region ideal for viticulture thanks to its Mediterranean climate and chalky, well-drained soils. We are welcomed by Angelos Tsangarides, who founded the winery in 2004 together with his sister Louiza. The Tsangarides family had been involved in agriculture and grape growing in Lemona for generations, but Angelos and Louiza decided to revive that legacy, not by selling grapes, but by making their own wine. They restored the old family home and built a modern winery around it. And they did a wonderful job. Not only does the winemaking area look impressive, the tasting room and terrace overlooking the vineyards are equally inviting. When we arrive, they’re already buzzing with activity.

The vineyards around the winery lie at elevations of between 300 and 500 metres above sea level. Together with the Ezousa River flowing through the valley, this creates a unique microclimate with lush vegetation and refreshingly cool nights. The family owns 30 hectares of land, of which 26 are planted with vines.

In addition, they purchase grapes from other local growers. The wines from their own vineyards are organically certified. The production of certified organic wines is around 400,000 bottles/year.

As many wineries on the island, the winery is embracing the trend of focusing more on indigenous grape varieties. Tsangarides aims to produce authentic, approachable Cypriot wines with a deep respect for nature and tradition, highlighting organic farming and the revival of native grapes like Xynisteri and Maratheftiko.

The vineyard next to the winery is currently planted with trellised Xynisteri vines, but Angelos explains that future plantings will be in the traditional bush vine style. According to him, strong vines are essential in this environment. He has experimented by planting Vasilissa and Maratheftiko together, two varieties he enjoys working with. But they’re not self-pollinating. So what if they don’t yield grapes? “If it doesn’t work out, at least I’ll have strong rootstocks for grafting,” he says.

After a quick tour of the winery, where stainless steel tanks gleam in various sizes, we head to the cellar. There, oak barrels line the walls and no fewer than 79,000 bottles are maturing.

Tsangarides – The Tasting

We begin with the Xynisteri 2024, made partly from estate-grown grapes and partly from purchased fruit. The wine is fresh and juicy – a light, easy-drinking start.

Next is the Vasilissa 2023, a rare and distinctive indigenous grape. “I estimate that only 15,000 bottles are produced on the entire island,” Angelos laughs. As it’s not self-pollinating, it must always be co-planted. The wine is fragrant and floral, with juicy yellow fruit, a subtle bitterness and structure from three months in new French oak.

The Rosé 2024, a blend of Xynisteri and Maratheftiko, was created in collaboration with Angela Muir MW, who moved to Cyprus after retiring. It has a light salmon hue, red fruit aromas, juicy character and a firm bitterness.

The Maratheftiko 2022 spent a year in French and American oak. It’s a vivid purple wine – juicy, with smooth tannins and generous fruit.

Then comes Mataro 2020 (a.k.a. Mourvèdre/Monastrell), introduced to Cyprus by Angelos’ father in the early 1980s. He was the first to plant it here, and the grape thrives in this warm, rugged landscape. The wine is full-bodied and rounded, with notes of dark berries, blueberries, and a hint of mushroom – elegant in style.

Another wine with a story is the Shiraz–Cabernet Sauvignon 2023. The Shiraz (75%) comes from the estate; the Cabernet Sauvignon (25%) was grown in the vineyard of the late Sir Edward du Cann, a former British MP and cabinet member under Margaret Thatcher. The wine is deep purple, showing almost-ripe cherry, juicy tannins, bay leaf and freshness. Angelos admits it “could use a bit more body.”

We finish the tasting with a Muscat 2021, made from grapes sun-dried for 10 days. With 70 grams of residual sugar and 1–2 years of oak aging, it’s fresh and round – sweet but not cloying, with lovely complexity.

But no tasting in Cyprus is complete without Zivania, the island’s traditional distillate.

Ya Mas!

All photography by Matt Wilson. To see the full album, visit the Circle’s Galleries.