Keith Grainger engages in deep conversation on a range of vinous subjects with winemaker Nicolas Seillan, and finds a reborn Saint-Émilion estate that has come of age.

How we define and identify quality in wines is a topic that I have written about extensively. Quality may be assessed using many criteria and, to me, one of the most important of these is that a wine should exude ‘a sense of place’. Put simply, we do not want a Bordeaux to taste like a Margaret River blend, even if it is made from ‘Bordeaux’ varieties, and a Saint-Émilion should not taste like a Margaux. Within Saint-Émilion (I’ll leave aside the satellites) many factors combine to give differences in style and quality between the châteaux, including incredible diversity of terroirs, particularly on the Côte.

As Bordeaux wine lovers and writers are very aware, there were upheavals in 2021 in the Saint-Émilion district. The announcement in July of the withdrawal of Châteaux Ausone and Cheval-Blanc from the classification system sent shockwaves throughout the district, Bordeaux and the fine wine world. Three months later this was followed by the conviction of Hubert de Boűard, co-owner of the Premier Grand Cru Classé A Château Angélus, for illegally manipulating the 2012 Classification. There was yet another blow upon the bruise at the beginning of 2022, with the announcement that Château Angélus had also withdrawn from the Saint-Émilion classification system. There have, however, been a record number of applications for the new classification that is taking place in 2022.

So, amidst the turmoil, it is great to write about a property where passion is to the fore, and the wine is crafted by a true vigneron. The words ‘hidden gem’ are sometimes overused by wine writers and critics, but certainly apply here. Château Lassègue was purchased from the Freylon family in 2003 by Barbara Banke, the late Jess Jackson, and Pierre and Monique Seillan. The quartet had already created Vérité in Sonoma, and began the rejuvenation of Tenuta di Arceno in Toscana. Pierre, whose roots lay in Gascogne, had long been a proponent of a ‘micro-cru’ approach to viticulture, and this philosophy was to become the heart of the three estates.

Just before the 2021 harvest at Château Lassègue, I had a long talk with winemaker Nicolas Seillan, son of Pierre. I have been both a lover and admirer of the wines for 10 years, and wanted to understand how the estate had been transformed. He tells me that following the purchase of the estate, the families focused immediately on the priorities in terms of improvements. Being really dedicated for the long term, they knew it would take time to accomplish their desired transformation.

They focused on the vineyards first, so the very first initiative taken by Nicolas’ father was to entirely avoid all herbicides. Of course, back in the 1990s, herbicides were generally applied in the Bordeaux region. If vineyards are on the flatland, it is relatively easy to avoid their use by ploughing the land, but on the hillside, you need expert management. Pierre hired fantastic people and the team were able to address all the goals that they were given. They wanted to keep the old vines, which they wished to retain to achieve the highest possible quality and complexity, so they had to work progressively. The vine canopy was elevated and over the years significant improvements were undertaken. The fruits of the efforts were realised, beginning with the vintages of 2009, 2010 and 2011. On newly planted parcels, the vine density has been increased to at least 5,500 vines a hectare, and sometimes to over 6,000 on the more recent plantations.

Detailed soil analysis was undertaken in order to design the cellar for the vinification. This enabled Nicolas and his father to select some specific tanks, also based upon what they had observed in the vineyards. Château Lassègue is located on the hills (Côte) of the Saint-Émillion appellation. Nicolas describes this as an ‘exclusive’ belt of land facing south and southwest. The myriad of terroirs stem from the Tertiary Era, which started 66 million years ago, and the Quaternary era, beginning 2.6 million years ago. According to Nicolas, each of the individual terroirs has its own energy, and Pierre notes that each gives its own particular message. Nicolas, echoing the words of his father, says: “We are just a servant of the soil. What nature gives you is in balance, and we try to give an artisanal product that expresses its origins. So, this collection of soils definitely brings different messages. We will keep them separate during the vinification.” This is made possible by the small tanks at Lassègue – the largest vat at the property is 7,000 litres, and the majority are 4,000-5,200 litres. Nicolas pays homage to the great ‘terroir’ properties of the Côte, including Ausone, Larcis Ducasse, Saint Georges Côte Pavie and Pavie. I have to confess that personally I have always found Pavie to be more of a ‘winemaker’ than a terroir wine.

Art versus science, Mozart versus Beethoven

I ask Nicolas about the artistic and scientific approaches to winemaking. “So, of course we do need some scientific approach – I don’t pretend to be an artist at all. I just try to organise all our resources with certain objectives that we have with the potential of the estate. Over the years I hope to gain experience to pretend to say I understand what I do.” I wonder if Nicolas is a trained winemaker and whether he studied oenology? Nicolas expounds: “In the Seillan family we don’t study oenology. My father didn’t go to school for oenology, and neither did I. The Seillans have been making wine for so many centuries in the Gascony area. It starts with passion. Passion gives us the energy. It gives us the motivation to act, to work. In answer to your question about artist versus scientist – immediately I saw your question I thought of the difference between Mozart and Beethoven. Mozart is a genius. He was able to write a symphony at six years old. Good for him, I applaud: It’s natural, in his blood. Beethoven worked his arse off. He worked so hard. When you see Beethoven, he was working so hard all his life. You see Mozart, he was having fun, having a beer. My teachers said: Nicolas, I am sorry, you have to work. You have to do exercises in your bedroom and if you cry, that’s good for you. But it is all passion; if you don’t have passion then don’t go into this activity for sure. Because again you face nature, and so many times nature will put some challenges to you, and if you don’t have the passion, don’t expect the road to be easy. Nature will take from you, it will take blood, it will take tears. But nature always give back; always, always, always. You make an effort and nature is not a bad partner; nature will help you so much. You need the passion and sometimes you do have some very big challenges to face.”

I talk with Nicolas about another Nicolas – M. Joly from la Coulée de Serrant. Several years ago, the infamous Loire winemaker said to me, “Keith, I don’t understand this word winemaker – what does it mean?” Nicolas Seillan almost explodes, “I agree. We are vignerons. Winemaker? – you put yourself in a silo. You have to have the vision. Vignerons are a very broad consideration.”

We return to the changes made by the Seillans in the cellar of Lassègue. Nicolas explains: “We can totally control each of our 31 tanks individually. We did a renovation of our barrel cellar in 2012. As we speak, we are finishing the construction of a second cellar. We are going to vinify, age and bottle our second label, Les Cadrans de Lassègue, in a separate location, about 800 metres away.

I ask Nicolas about the ‘globalisation’ of wine styles, which has perhaps taken place in Saint-Émilion, and how does he think that producers should be working to express their terroirs. “You have a very good point. Until the recent years nobody was saying it, but today there is, I believe, the consideration, as we say, to put back the château in the middle of the village.” Responding to whether the impact of climate change is negating ‘terroir wines’, Nicolas responds, “it depends if you are risk-averse, or not. You have to accept pressure, and you have to accept consequences from nature. I’m talking about variances in yields in particular, and during the recent years sometimes, maybe because some estates have a more financial rather than long term approach, there is pressure. They can be owned by investment banks; that is not to say what they do is wrong. I think it’s important to really respect our origins. We make a Saint-Émilion. Saint-Émilion is about elegance; it is about the expression of the Cabernet Franc, and we have ways to respect these objectives by avoiding heavy extraction and making too muscular wines. That being said, we do have the expression of the sun, and some power that Lassègue expresses, along with the elegance, balance and finesse. We do have up to 10%, sometimes 15%, of Cabernet Sauvignon. We are extremely meticulous to make sure we retain the elegance; we want to make wine to be enjoyed, and not one of those that sometimes are almost undrinkable.”

A sustainable approach

The estate has taken numerous measures to improve sustainability, in addition to the abandoning of herbicides, and is obtaining HVE (High Environmental Value) Level 3. This is the highest level of certification, and the vineyard must have high biodiversity and a low level of inputs. Nicolas explains: “I consider that HVE 3 brings more to the community at large… Since the beginning we have had Zones de Non Traitement (ZNT) of 5 metres. Even if we didn’t have the certification in the early years, we were acting with very similar considerations.” I ask Nicolas how the estate is adapting to climate change. He says that when replanting has been undertaken, more Cabernet Franc has been used. “Cabernet Franc has shown us some excellent results so far in challenging conditions, with the heat and the drought, compared to Merlot. There are some very interesting results in terms of alcohol. We decided to focus on Cabernet Franc for several reasons: number one is the fact that Lassègue is equipped to receive Cabernet Franc, and secondly because of what we’ve been observing with the coming global warning. Six to seven years ago we took those decisions already to re-orient the plantations with Cabernet Franc for that specific reason. So, I don’t know what the other appellations might do but maybe some may reconsider some lost or forgotten varieties.” He says that Lassègue is fortunate in being largely on pure clay, which retains 40% water, and releases it progressively.

We discuss the increase in alcohol levels in recent years, and in response to my comment that I like to drink wine rather than just sip a highly alcoholic concoction, Nicolas: remarks: “What is a good bottle of wine? It’s an empty bottle.” He states that they use a selection of cultivated yeasts. I have been researching the use of non-Saccharomyces yeasts, to limit alcohol production to perhaps 13 or 13.5%, and Nicolas notes, “like Bordeaux used to be. You are a classic connoisseur of Bordeaux. Bordeaux, when you go over 14%, you have to ask questions to yourself. Of course, at some point something is changing – Bordeaux used to be 12.5%.”

I have always found Lassègue to be a deftly extracted wine, so I ask about the techniques used. “There is no protocol. We adjust to each vintage. We do some cold soaks: these bring a lot because you can capture the colour relatively rapidly, and you protect your grapes in the tank. When I say cold soaks, we can go down to six degrees. Cold soaks may be 3 or 4 days – this depends upon the colour – sometimes 1 or 2 days, depending upon the varietal. In terms of pump-overs, we try to be gentle, sometimes just to keep the cap wet. We don’t do pigeage [punch-down], which can be quite violent sometimes. Two pump-overs per day is the maximum per tank. We are very careful with extraction,” says Nicolas.

From donkeys to racehorses

“There is no formula. You have to face the reality of each vintage. You cannot make Château Petrus 1982 every year. You cannot turn a donkey into a racehorse. However, I love donkeys – they are beautiful. Take the 2007 vintage: you know, Bordeaux 2007 was shot before it was released. Later people came back to this vintage: it is a beautiful, elegant wine. You measure the performance and capacity of an estate in the difficult vintages. If you look at the frost that has affected Bordeaux in recent vintages, and if you look at the areas that were not affected by the frost, then you rediscover the old map of Bordeaux. Bordeaux used to be less than 60,000 hectares. Jess, Barbara and my parents were very proud to have a presence in Bordeaux, but they picked what they believed was a jewel. Lassègue used to be, for 260 years, in the same family. It was this estate, not another one – it is one of the ancient estates of Saint-Émilion, not by accident: elevated, facing south to south-west, on the Côte, with a collection of more than 15 different types of soils. When I say it is traditional, I go back to Julius Cesar, when surveying the blocks of land: here I will put the pigs, here the cows, here the cereals and right there I will put a little block of vines. He was considering the micro-crus – we did not invent anything, my father and I. The poor little legionnaires who were retiring with one arm less – they were considering the micro-crus,” asserts Nicolas.

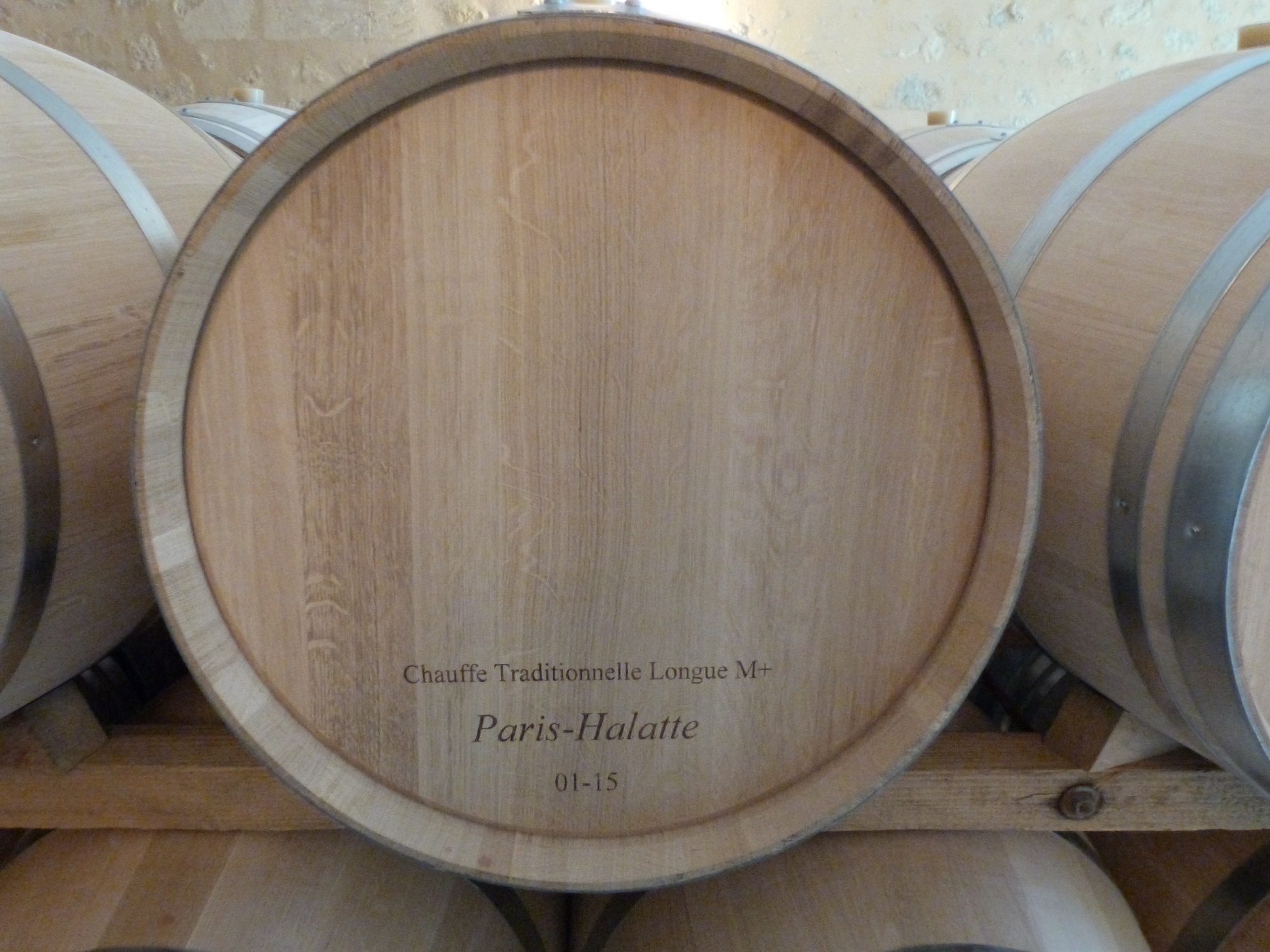

When I was last at Lassègue, I was amazed by the large range of cooperage oak in the cellar, including several sources unknown to me. I ask Nicolas what he is looking for when selecting barrels, and what does each source add to the blend? “This is a subject where I have the most passion. Oh my god! I will try and stay as concise as I can. It’s my favourite subject, but I am going to stay calm. Jess Jackson and Barbara understood relatively early the importance of being able to control the sourcing of the staves utilised to construct the barrels. With that in mind, they decided to invest in a stave mill. This happens to be located in the northeast of France, in the Vosges area – the best area for stave mills, because you need the four seasons. When you dry the staves outside, you need wind, rain, sun, hail and snow; all the natural elements that clean the wood of certain tannins. The mill is at Monthureux-sur-Saône, a tiny little village. Jess Jackson gave me my first mission when I joined the company in 2003. He said, ‘Nicolas, go count the staves.’ Do I want to count the staves in winter, in the snow? ‘You learn there’, Jess said. And there I met the most amazing people: talk about passion and talent. Think about this activity: you make a decision today and it will be 10 generations after you that people harvest the decisions you are making. My father realised the fantastic opportunity to source from different areas inside the forest. Because when you think about it, as vignerons we are super-proud of our terroirs, blah, blah blah. But when you think about an oak tree, 600 years old: talk about the importance of terroir! So, we are able to select inside the forest based upon the terroir. As you can imagine, if the tree is growing in a very humid area, it will grow too fast and the grain will be too wide, and if you are at the edge of the forest it is twisted due to the wind. You are looking for fine, tight grain. The selection of that we can make inside the forest and this has taught us a lot. At Lassègue, we have barrels from about 20 different forests: it’s crazy but each is bringing an additional layer of complexity in the blend. We use very light toastings and try to consider the oak expression and not only the toasting expression. That’s extremely important. We have a cloud of solutions and many, many other dimensions. The challenge for the vigneron is to consider where to position yourself when you make decisions on the different axes. We also have to be careful the oak doesn’t cover the fruit. In our family the oak is like a ghost in the castle.”

I enquire about interventionalist winemaking, including free and molecular sulphur dioxide levels. “My introductory sentence to you would be wine without human impact is called vinegar. We do undertake sulfur additions, but we happen to be very light. During the ageing, when the wine is in barrel, if we go over 15 mg/l (free SO2) it’s high. Usually I am closer to below 10 and the when I do my lab testings, the laboratory calls me ‘are you crazy, it’s way too low.’ It’s a global consideration. First of all, we do the malolactic in tanks. When the wine is put into the barrels it is dry, completely finished and has been racked several times. We have a very pure and clean wine. We keep the wine in the barrels for not over 12 or 13 months: maximum 14 months during ageing which is not long, as you know. We don’t keep longer. We aim to have the most optimal relationship with the wood. We do use some 1 and 3 year-old barrels too. That being said, I don’t need to put too much sulphur with these considerations. If you put sulphite over a certain limit the wine is, as you know, closing itself. Not only is it difficult to taste, but the relationship with the barrel is not optimal at all. If you want to be very effective and efficient during your ageing, it is preferable to avoid too high sulphite additions.

You also have the consideration of the quality of the harvest. If the fruit coming into the cellar is in good condition, you are not necessarily using sulphite. It’s a global consideration. You spoke about Brett – Brett sometimes is in the vineyard. If you are careful with the type of pruning, not to carry too much fruit, if you’re careful with the picking date, not to be over-ripe and having some quality issues, if you do an impeccable sorting as we do, then you can start to consider to really minimise the sulphite additions. But again, my point is that not using sulphite is something I never do. It’s not something I recommend, because I don’t have the experience.”

The classification question

We move on to discussing the Saint-Émilion classification. Lassègue has applied to be classified in 2022. I ask how important Nicolas sees the classification as a recognition of quality, and whether with the withdrawal of Cheval Blanc and Ausone, it is less relevant. Nicolas explains that the Lassègue team really took a long view, and took the time to prepare the vineyards and the winery and to prepare the presentation. “We don’t want to force anything. The classification is, as you say, a sensitive subject. You know, honestly, we have to consider it for what it is. One of the reasons why we were not in a hurry to consider the preparation of the estate is because we strongly believe in our capacity to communicate and to convince our partners, and again when they come to the estate they realise the location and everything we have been talking about. When people come to the estate, they do realise: oh my God! It’s not classé?

It was not classé with the previous family, the Freylons, for their own reasons. Of course, Lassègue benefits from a classification consideration but at the same time it would be a mistake to put the classification at the pinnacle of everything. To us a Grand Vin is a wine that respects its origin. We have the communication considerations, that is important, but this classification to me, to us, is only one tool to consider. The great connoisseurs of Bordeaux don’t need the classification to consider Château Tertre Rôteboeuf as a great wine. They don’t need a classification to consider the great wines of Pomerol. Again, I think it’s an important indication that can help certain people who don’t necessarily know the appellation well. We have to take it calmly. I don’t see the classification as being weakened. It is one possibility to communicate, but it is certainly not the only one.”

Crucial Cadrans

Our conversation switches to the ‘second’ wine, Les Cadrans de Lassègue. “It’s extremely important. The second wine in an estate in general is critical – it’s in the core of the activity of an estate. It does express, from our standpoint, more the foothill blocks versus Lassègue that is really in the hills. It’s also the home of certain blocks: if the vines are too young, they do not go into the Grand Vin and Cadrans is a fantastic house for this section because it brings the freshness. The second label and the Grand Vin always work together. The Grand Vin gives the tools to the second label to really exist and the second label allows the Grand Vin to find a house for Lassègue quality. But again, for the balance of the estate, it is to us very important. But we don’t have only second label, we also have ‘select outs’ that don’t go in Les Cadrans, a ‘third wine’ called Château Vignot, because we don’t want to inflate the production. Les Cadrans represents 30% to 40% of the estate. We are extremely careful with the quality of Les Cadrans, because we really consider it as an ambassador of the Grand Vin. Collectors may have their first introduction to the estate, or some people who cannot afford the Grand Vin for their first experience, so we have to be very serious and very careful with maintaining the highest possible quality with Les Cadrans.

I ask Nicolas about the greatest wines he has ever tasted. “I will go back with my father to when I was studying finance, and I learnt about Sauternes. Here you have God and just below you have Château d’Yquem, and then you have the rest. I had Château d’Yquem 1990. After that……….” There is a long exhalation. “You have this kind of experience that you really, really consider the artistic approach, at this level, when you think about the considerations they have when they pick. By the way, if one day I need a heart transplant, make sure they take one from a vigneron of Sauternes. You know, when they wait to harvest, and everybody around has harvested – they wait and wait to optimise, so they must have very strong hearts. My great memory is of a tasting of Sauternes, when we had a fantastic collection and finished with Yquem. Then, I understood the complexity of Yquem. I realised the importance of the architecture of the wine. There are also some great champagnes from small houses that put you in a position to say ‘wow’. Some very small houses do something to me – they can make some amazing qualities. But yes, I think about that 1990. I have, of course, some fantastic Bordeaux’s, but I go back to Yquem because it’s so special.”

Our long conversation concludes with me asking about tastes in music. Having discussed Mozart and Beethoven, I presume he’s not into garage music. “Yes, it’s classical for me. I studied piano for 12 years and my teacher was classical – a little Mozart and a lot of Beethoven.”

And so to the wine in the glass. I am now sitting in my home in the Charente-Maritime, about 60 miles from the Château. It’s a chilly evening, but the log-burner exudes its carbon neutral warm glow. And the wine, the 2015 Château Lassègue, having spent an hour in a decanter is really singing. Without doubt, it’s Mozart, not Beethoven. It is perhaps the 2nd movement of Symphony No. 40 – the Great G minor Symphony, as it reveals itself layer by layer. The tertiary notes are already developed: Christingle orange, tons of leather, mace and cloves. The texture is silky, the wine is elegant but with underlying power. Deftly crafted, and with a real sense of place: Château Lassègue.