In the first of two articles, Wink Lorch leaves the French Alps and veers into volcanic mountain territory to explore the Côtes d’Auvergne, a wine region that has risen from the ashes, and is joined by fellow CWW member and Loire expert Jim Budd. The second instalment is due to appear in September’s edition of The Circular.

Having been lucky enough to spend lockdown high up in my French Alpine home, in June once things eased and restaurants reopened, I ventured out on a road trip, including a visit to the volcanic area of Côtes d’Auvergne. This small wine area, technically part of the Loire wine region, is making ripples (not quite waves) for its Gamay and Gamay-Pinot blends.

Especially after the months of looking at a screen, the prospect of visiting the first ‘new-to-me’ wine region for several years was alluring, but I needed company. Who better than Loire expert Jim Budd and his partner Carole, who had been locked down in their Touraine home? Also joined by friend Lyn Parry, a travel, food and wine book editor and writer, based near Lyon, we rented a self-catering gîte for three nights in the quiet village of Authezat – we were the owners’ first guests since lockdown. Our complementary interests and specialities made the trip even more interesting: for Jim and Carole, this was a belated return visit to the Côtes d’Auvergne, one of the four wine areas of the upper Loire; for me the attraction was to discover another mountain wine region, and for Lyn, the focus was on the gastronomy and general tourism, alongside the wines.

We built the trip around a day that had been meticulously organised for us by Léa Desprat of the region’s largest producer Desprat Saint-Verny, alerted to our visit by Richard Kelley MW of Dreyfus Ashby, the company’s UK importers. Richard has long been a fan of the Côtes d’Auvergne and wrote an incredibly detailed ‘chapter’ for his online Loire wine guide, following his visits there a decade ago.

The growing interest in Côtes d’Auvergne wines has been partly due to the developing intrigue for so-called volcanic wines, and partly due to the number of natural winemakers based there – Gamay, Auvergne’s main grape variety, is ideal for low-intervention winemaking. However, Jim and I decided to focus on some well-known, easier-to-visit non-organic and organic (but not necessarily natural) vignerons to visit alongside Desprat Saint-Verny.

Côtes d’Auvergne: a brief educational slot

The vineyards of Côtes d’Auvergne are in the department of Puy de Dôme, in France’s Massif Central. The scattered vineyards stretch for 80km north to south with the departmental capital, Clermont-Ferrand (home to the Michelin tyre company), roughly in the middle. Approximately 400 hectares of vineyards include 270ha in the eponymous AOC and a further 80ha categorised as IGP Puy de Dôme and 50ha as Vin de France. They lie at altitudes of 350m–540m, mainly on gentle slopes above the Limagne basin, east of the volcanic Puys mountains. The last time these volcanoes were active was about 8,000 years ago, but the lava flows they created and the debris they left make for very varied and unusual soils. The Puys, as they are known, also help to create a rain shadow, making this quite a dry vineyard region, and provide the geography for a warm Foehn wind effect, which moderates the semi-continental climate. Spring frost and random hailstorms are a big hazard; as everywhere, mildews can be a problem. Climate change has brought more worrying loss of crop due to drought, as occurred in 2019.

The River Allier, an important Loire tributary, runs through the south-eastern part of the area and allowed wine to be transported to the courts in Paris a few hundred years ago, when the wines enjoyed quite a reputation. There is plenty of evidence that vineyards have been established since Roman times, but the other significant piece of history is more recent. Until the 19th century, Pinot Noir was the main grape, but Gamay, producing higher yields and ripening more reliably, overtook it and this held the region in good stead when phylloxera began its path of devastation in France. Being so isolated, the Côtes d’Auvergne vineyards were spared phylloxera for almost three decades, and more Gamay was hastily planted, as it was ideal to provide wines for thirsty markets around the country, while other regions fell to the disease. By 1890, the Puy de Dôme was the third most planted department in France – after the Aude and Hérault – with around 45,000ha of vineyards, only about a quarter less than the whole of the Loire Valley’s vineyards today.

Phylloxera eventually destroyed the vineyards and the region struggled to recover, with mildew attacks, the World Wars, industrialisation, the general difficulties of working in a hard landscape and climate all adding to its demise (not that dissimilar to the French Alpine regions to the east). Nevertheless, Côtes d’Auvergne gained VDQS in 1951, but it took until the 1990s for quality to improve. CWW’s President Rosemary George MW wrote five pages on the region in her book French Country Wines, published in 1990, concluding that she felt positive for the region’s future as she left after several vigneron visits. (Incidentally, although of course it is out of date, this book remains unequalled for its detailed snapshot of France’s ‘country vineyards’ 30 years ago – it covered all the vineyards of southern France, and the country’s other smaller wine regions.) When the VDQS category was due for the chop, after a long administrative struggle in 2011, Côtes d’Auvergne became AOC – and it has charted a remarkably similar path to that of the Bugey AOC.

Within the Côtes d’Auvergne AOC, Gamay is the dominant variety, followed by Pinot Noir and finally Chardonnay (introduced late into the region), with red wines accounting for 60% of production, rosés 25% and whites just 15%. For both reds and rosés, Gamay must make up at least half of the blend, so any pure Pinot Noirs must be labelled IGP Puy de Dôme; the latter category is also used in particular for Syrah, with plantings increasing, and for several white varieties to complement Chardonnay.

There are five Côtes d’Auvergne crus, all but one exclusively for reds – as well as being defined geographically, they require slightly lower yields and higher minimum alcohol levels. North of Clermont-Ferrand, the crus are Madargue (near Riom), Châteaugay (the largest) and Chanturgue (effectively within the city boundary). To the south are Corent (for rosé only) and somewhat further away near Issoire, Boudes, almost as planted as Châteaugay, and home to the steepest and highest vineyards. The cru vineyards account for just over one-third of the AOC vineyards. Otherwise the most planted areas we saw were in St-Georges-sur Allier (where we visited an important associate of Desprat Saint-Verny) and those close to where we were staying below Montpeyroux, around Authezat and Neschers.

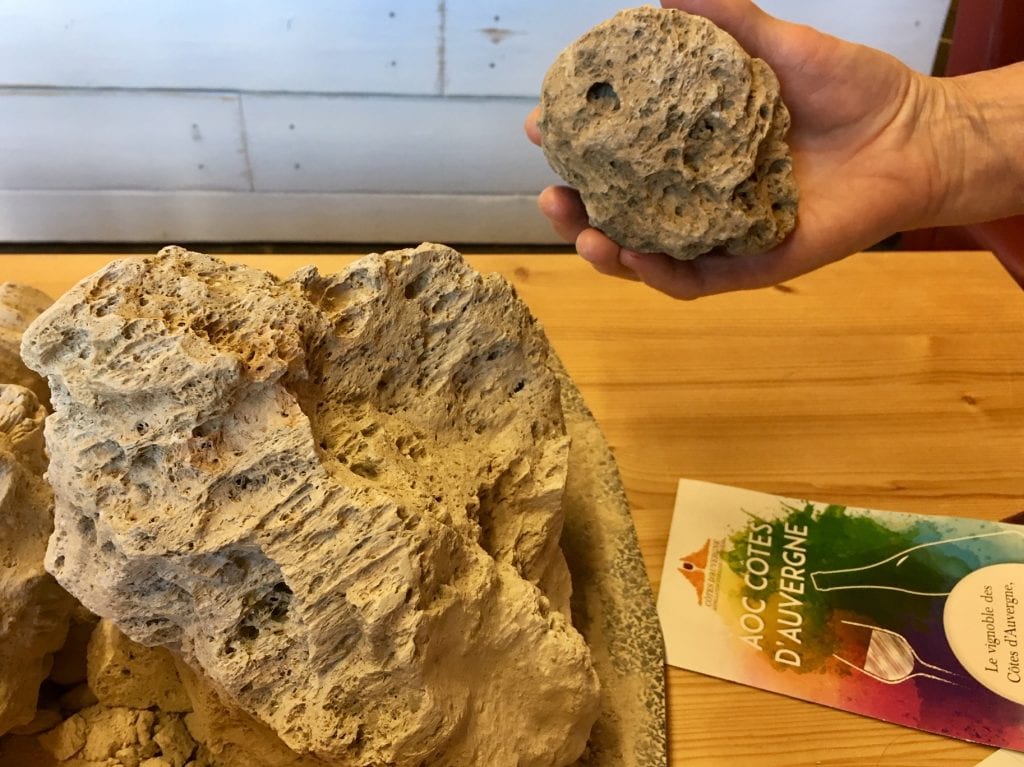

It is no surprise that the geology and soils are complicated. Volcanic rocks are present in various forms across the region; occurrences of basalt are widespread. In varying places, the bedrock can be clay-limestone, marl-limestone or granite. And as we were to see in Châteaugay, there are examples of what is known as ‘inverted relief’, which in summary means volcanic lava that had once been on the valley bottom, forms a plateau at the top following a period of uplift and subsequent erosion. And we were to see pépérites (small stones made up of volcanic ash) in Châteaugay; and terres ponces (soil covered in featherlight pumice – described in Alex Maltman’s excellent Vineyards, Rocks & Soils as ‘volcanic froth’), near the village of Neschers. Rather amiss perhaps, as we all enjoyed the rosés, we never went to visit the vineyards of Corent, which are effectively on a volcano, and where pouzoulane (pozzolan – a red siliceous volcanic rock) is prevalent.

Auvergne producers

The region has around 35 individual producers (some of them small négociants), and a further 60 are vigneron associates of Desprat Saint-Verny, the former wine co-operative, which accounts for about half of the region’s production. In the next edition of the Circular, I will write about the producers and vineyards we visited and provide a snapshot of the wines we tasted and drank, not forgetting a mention of the food. In the meantime, Jim Budd has already written a blog post on organic vignerons Yvan Bernard in Montpeyroux and Domaine de Miolanne in Nescher, alongside two posts on Desprat Saint-Verny. He promises future posts on Annie Sauvat (with whom we toured the Boudes vineyards) and her neighbour, David Pelletier, and on Benoît Montel in Riom, who I was not able to visit. See his blog Jim’s Loire and Les 5 du Vin, for which he is a contributor.

Part 2 will be published in next month’s edition of The Circular