Marisa Finetti is not only blown around, but also blown away by Nebbiolo from the Alpine foothills in the northern part of Piedmont, and the incredible effort and unswerving dedication taken to grow it.

The wind snapped my umbrella inside out. The impression of Carema while standing on the edge of the dramatic hillside on this blustery day was quickly leaning toward sheer intensity. Federico Santini, winemaker, and owner of Muraje, shared his sturdy, oversized umbrella as he talked about extreme mountain viticulture (and weather). He and his wife, Deborah, are among the very few restoring this land in the northern part of the Piedmont region of Italy. Their 1.4 hectares of vineyard – some parcels as small as 50 square meters – are like a 40-piece puzzle scattered throughout the entire Carema area. Piece by piece, they are not only building their dreams; they are putting this historic area back together.

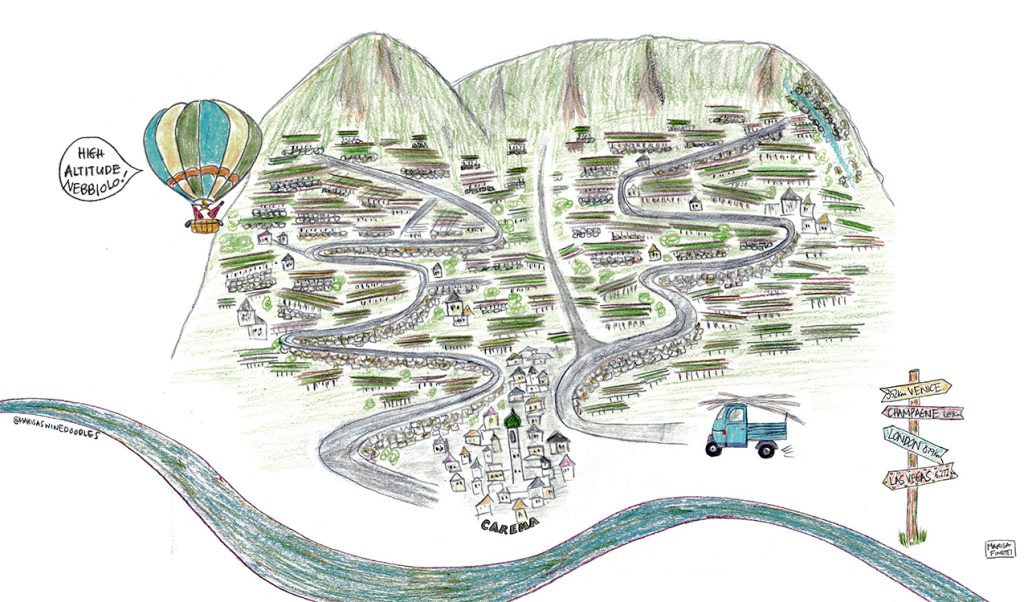

As we looked straight down this hilly terrain made for mountain goats – the undisputed masters of terrifying heights and cliff hiking – the spectacular view revealed a patchwork of vineyards carved into stone mountain terraces. I should have brought my all-terrain boots and a walking stick, too.

Carema’s vineyards are precipitously steep. What drives wine producers like the Santinis to challenge gravity-defying agriculture when growing grapes in Carema is painstakingly difficult? The soil is brought up from river banks. Everything is done by hand. The vineyards need repair from decades of neglect. There isn’t enough profit to be made yet, so many producers hold other jobs. Tenaciousness is a must. But looking at the positives: breathtaking visual splendor, the prospect of alpine Nebbiolo, farming has been done here before, and fortunately for Nebbiolo fans, a passion for restoration and renewal by a small group of winemakers is taking place right now.

All that remains today in this tiny appellation located in the foothills of the Alps encompasses 18 hectares chiseled into the mountainsides. Just a few years ago, there were only 13 hectares. The trend for Carema’s renewal is in motion. Barely known internationally due to its still-limited production, wine lovers have held this area in great esteem for centuries. Carema sat on a strategic point on the military road to old Gaul. It is believed the Romans encouraged settlement by terracing vineyards. Winemaking became famous as early as the 16th century, and by the early 1900s, the area under vine reached upwards of 120 hectares.

By 1967, while San Francisco was enjoying the summer of love and Sgt. Pepper’s was topping the charts, Carema was becoming one of Piedmont’s earliest wines to attain DOC status. But the affinity for this treacherous land had already fizzled away in the early part of the 20th century, when industry came to nearby Torino – first for textile manufacturing, then for the automobile boom.

Crumbling Carema and then its comeback

Carema was eventually abandoned, as evidenced today by crumbling terraces made of rock wrenched from the mountain and brambles of shrubs and trees emerging in places where Nebbiolo vines once thrived. The morainic soil – typical of the ice age – still remains from when it was carried up the steep slopes from River Dora Baltea by early farmers.

These forgotten sites blend into the hillside like a storybook in an old library wall, ignored for decades, hauntingly mysterious, longing to be cracked open again. However, through Camera’s economic highs and lows, there was one single producer, Ferrando, who kept the wine-growing areas of Alto Piemonte alive as early as the 1900s. Sure, locals always grew grapes to make wines for themselves, but Ferrando saw significant potential.

At Ferrando’s modest estate in nearby Ivrea, Roberto Ferrando pours his family wines and talks about their history. His face – expressive, congenial, and authentic – is seemingly characteristic of someone who has spent his whole life building upon the family heritage while ankle-deep in vineyard soil. He says his grandfather, Giuseppe, fell in love with Carema and decided to invest his time here in the late 1950s.

“At the beginning, he worked with locals in Carema to purchase their grapes, but by 1960, our first vintage was produced with full winemaking [and viticultural] control,” says Ferrando. Today, the Ferrando name is almost synonymous with Carema. In addition to the Produttori di Carema cooperative, established in 1960, Ferrando’s family continues cultivating its vineyards on the mountain terroir in an amphitheater that sits in the very shadows of Monte Bianco.

“If Carema is like this today, it is thanks to this winery [Ferrando] that has been producing great wines for so long!” says local winemaker Vittorio Garda. “Luigi Ferrando is a fantastic piece of history of Carema.” Garda, like the Santinis, is among the new breed of winemakers who have recently emerged with dreams to reclaim the vineyards of Carema. “The important thing is to get to the goal, even slowly,” says Garda. His winery, Sorpasso, which means to pass or excel, is an homage to Aesop’s fable, The Hare and the Tortoise. “We and the other young producers, like Gianmarco Viano from Monte Maletto, got involved. We are planting the vines, cutting the grass, doing the shoulder treatments, hoeing, maintaining the wooden arbor structures, and tending the stone walls – all by hand. Slowly. Like a turtle!” says Garda.

Garda was the first of the new wine producers to arrive. He and his partner, Martina Ghirardo, started in 2012 when they rented their first vineyard in the area. Now they own one hectare, with their first Carema DOC in 2016. “My grandfather had a restaurant with a butcher shop. He was an enthusiast and wine merchant,” says Garda. “I followed in his footsteps and chose Carema because it’s fascinating.”

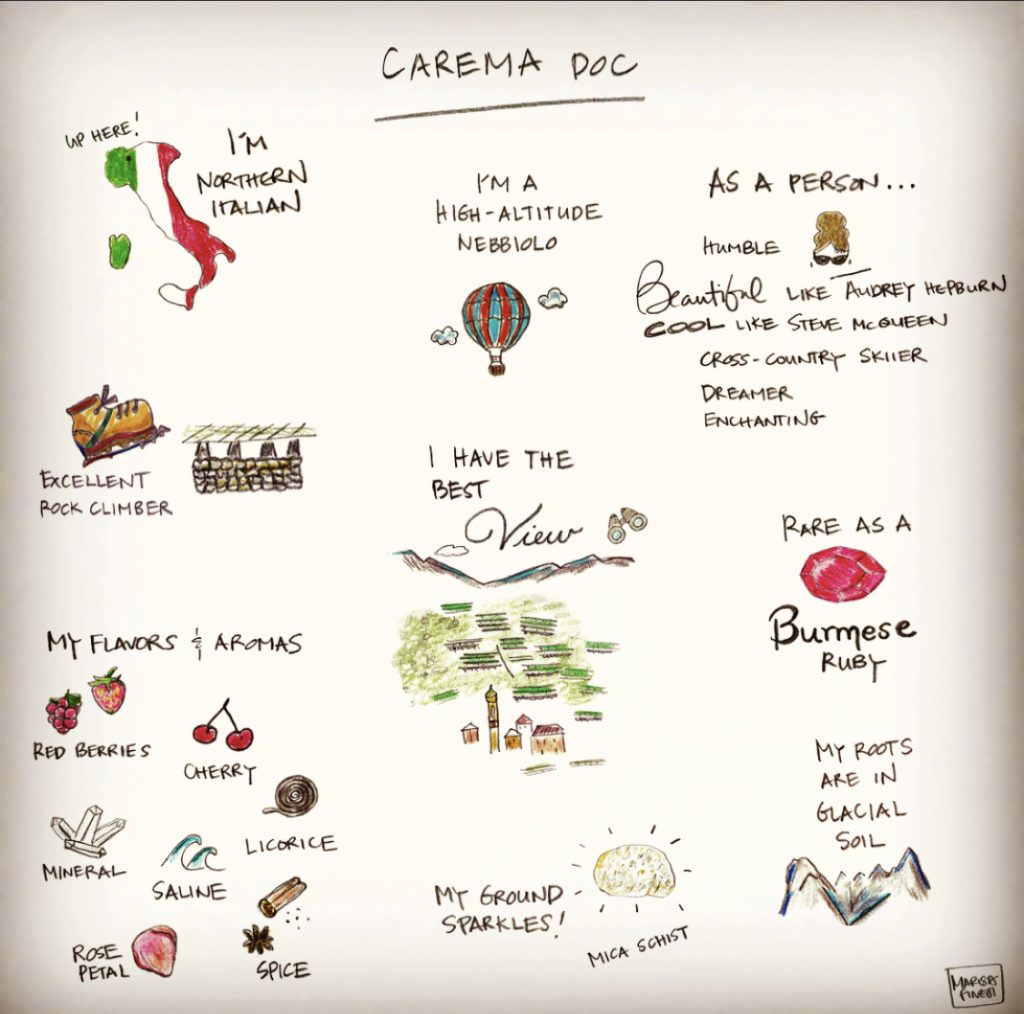

Carema’s own clone of Nebbiolo, plus rare Italian varietes

With a goal to protect and promote Carema’s viticultural tradition, Garda and the other newcomers champion the native Picotendro grape (a biotype of Nebbiolo), plus he grows parcels of seldomly-seen native Italian varieties such as Neretto and Ner d’Ala.

Among the tapestry of vineyards, Carema’s territory reaches high up the sides of the mountain along ridiculously steep and narrow roads. At harvest, grapes are gathered by hand by only the sure-footed, and then carefully transported in small baskets. Could these wine producers have picked a more accessible place to make wine? They say it’s worth it.

“At the end of the project, when I taste my wine or the wine of my friends, it is worth the work every day,” says Garda. “We do our work without an awareness of our role in the revival of Carema. We believe that Carema is one of the most special places in the world to make wine. Where the stones, the sand, the wood, the wind, the uphill paths, the walls, and the toil come together in a wine whose terroir and wine are the exact same thing.”

Moving mountains gracefully

The product is a wine that embodies Nebbiolo’s heart and essence from Carema – one that showcases grace over force. Where Langhe Nebbiolo wines might have the muscles of a ballet dancer, Carema has nerve and energy. Furthermore, Nebbiolo’s remarkable penchant for site-specificity lends to wines that elegantly express the terroir. And while the area under vine is minuscule in Carema, several crus are already being established. Airale, Siey, and Silanc, among others, potentially feature high-quality Nebbiolo vines with unique exposures, alpine microclimates, and soils.

And to Airale, we went. But one needs good shoes to explore this mountain, especially for the crooked stone steps that jut out from the terraced walls. Needing some assistance on my part, winemaker Matteo Ravera Chion of Chiussuma lends a hand. In 2016, he joined locals Rudy and Alessandra Rovano to create Chiussuma. Their three-hectare vineyard grows Nebbiolo and Ner d’Ala vines trained on topia, chestnut wood trellises on granite/mica pillars. Many are still being constructed. It’s a small production and an arduously slow process.

We walked past the estate’s three friendly donkeys, climbed to an upper terrace, and got a closer view of the Chiussuma Falls, after which the winery is named. Once up on top, the feeling of Carema’s remoteness is real and defined by a network of vineyards with minimal infrastructure. To be able to make wine here again is a hugely ambitious proposition. But, together with Chiussuma, now there are eight producers and counting.

On this day, the waterfall is full and roaring, reminding me of the pure energy being generated in this pocket of the world. Their passion for renewal is inherently invigorating and just like the waterfall, these young producers have got the mountain in their flow. Furthermore, they are truly moving mountains.